Inside Art Episode 5: Katie Merz

Published:

June 1, 2023

For this episode I talk with Katie Merz in her Brooklyn studio. We produced a show of her work in my gallery in Williamsburg 25 years ago, and it was featured on the front page of the NYTimes Arts section with a rave review by Roberta Smith.

We talk about her new work and its similarity to the experience of walking through that show in 1998, and how she feels at home working on city streets and using architectural facades around the world as her canvas.

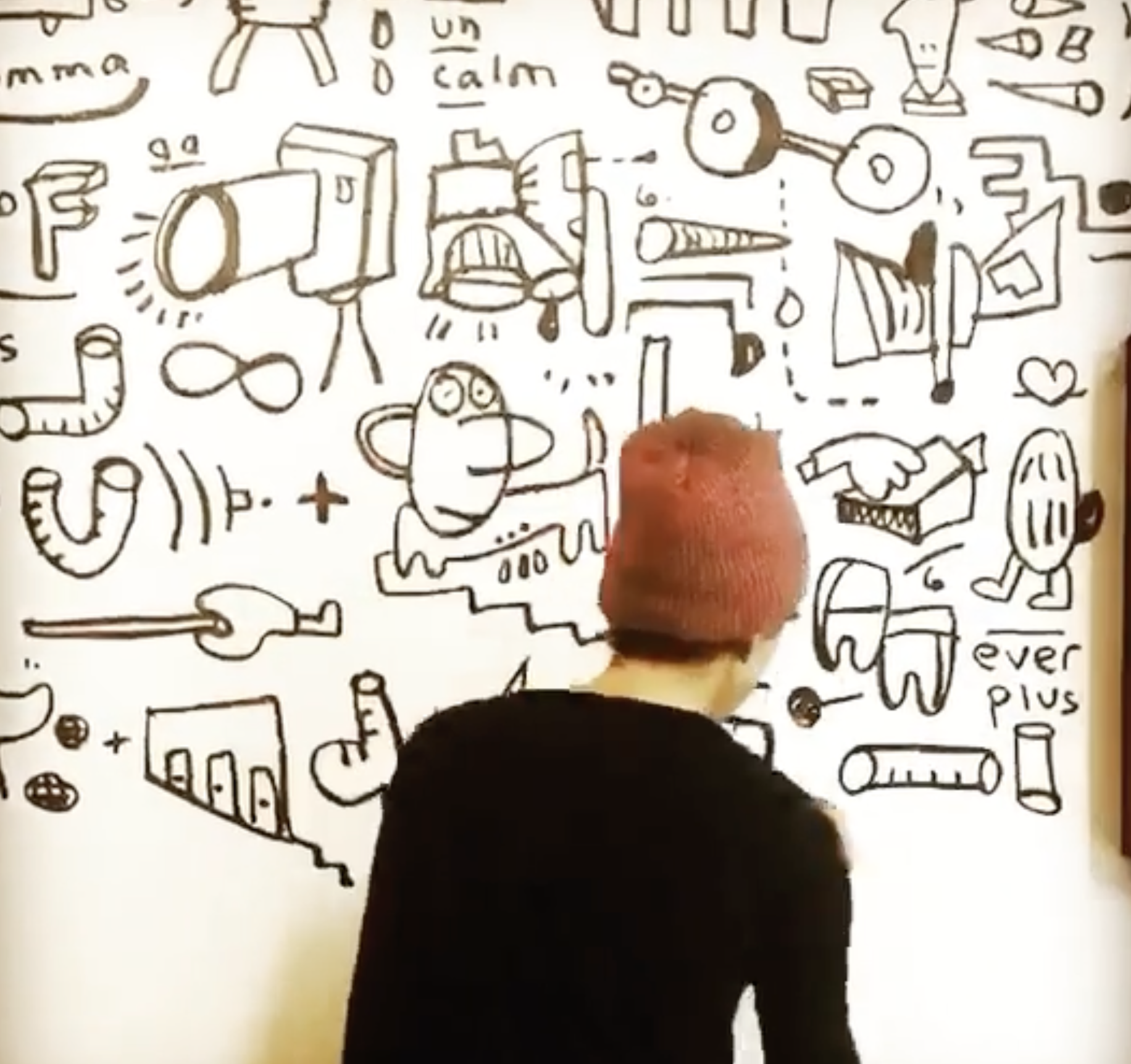

Merz’s visual language often references cartoons, graffiti and modernism. She grew up influenced by surrealism, modernist art and architecture as well as the neighborhood she lived in. She also talks about music and learning the violin as something that informs her way of drawing and understanding layers in space.

Her work belongs in museums and galleries, but I am so glad she is working on buildings and in public spaces where more people can see it and come alive as they interact with her work.

Listen on Apple, Spotify, Amazon Music, Google Podcasts or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

“A collaboration is two people seeing the third thing. So if you never saw what I was seeing, then the show would’ve never happened.”

About Katie

Katie grew up in Brooklyn and earned a BFA from the Cooper Union School of Art. She has exhibited her work nationally including the Brooklyn Museum, and been a recipient of the Pollock Krasner Grant and The Robert Motherwell painters grant. Influenced by Brooklyn, cartoons, architecture and modernist sculpture, she strives to refuse hierarchies in her pictorial language. Her recent public work creates a narrative convergence of graffiti and language using urban hieroglyphs and an animated library of words, math and random visual symbols.

Artists mentioned

Architects Mary and Joseph Merz

Charles and Ray Eames

Eames House, Los Angeles

Galleries & Institutions

Velocity Gallery / Roberta Smith review NYTimes Nov, 1998

Cooper Union, School of Art

Katie’s links

Website: katiemerz.com

theflatbushmural.com

Instagram: katiemerz

muralat80flatbush

Images mentioned

Please rate and review this podcast on Apple Podcasts

Thank you for your support, it helps share the podcast with a larger audience.

Inside Art Podcast, Episode 5 with Katie Merz

Sarah Rossiter Hey, Katie Merz. Welcome to Inside Art Podcast. I'm so excited. So you're in Brooklyn…

Katie Merz. Me too. You're like a sister from another decade.

SR I know. I was just looking it up. I was like, when did we work together? 1998.

KM '98?

SR Yeah. Roberta Smith's review online from The New York Times. She reviewed your show in November 1998. So it must have been October/November.

KM It was. I remember that really well. It was not too cold. Yeah. I have such clear memories of that.

SR So for everyone listening, I had a gallery called Velocity and Katie did an installation in the space and it was really beautiful. Paper was on the floor and you had these strings that went all over the gallery and you were hanging photographs like on a close line. And as people traversed the gallery, it felt like they were in these photographs. And the photographs themselves were really immersive. They were shot in your studio, closeups of materials, paintings, pigments, ripped paper. They were gorgeous.

KM Yeah. They were so...internal. I mean, I remember doing them and going into these days without talking to people. Yes. And I'd set up my studio in my apartment and I'd bring in colored sand and– I would keep it all in one room—you couldn't really walk in, I made a path.

SR I remember that room.

KM Yeah, that's right. Yeah. Because you came over and you're like, "Okay, hold on a second. Let's do a show."

SR It was so good. And you would use mirrors too. So it was very disorienting, like what are we looking at? What's the scale? Are we in a painting? Are we in a drawing? Is it a collage? It was like a whole other world. It would be a very small thing like sand, but it would feel like a landscape.

KM Right. Exactly. You know, it's funny because I have some of those photos here and there's a little piece of spaghetti, like a little shell, like a pasta shell inside of a picture of a room. So you couldn't really tell what was what because the photograph flattens everything. And then like a hand is in it. So I always think it's like when you're dreaming, there's no scale, there's no scale reference. You're just in the stream space. And the same with time. Like, there's no reference for time in dreams, but things are happening in that sense of time and scale. So I just thought, "This is what it's like in a dream." If you took a picture of a split second in a dream, that's what it would look like—well, yeah. You know that because I remember trying to articulate that. But another thing, Sarah, is a collaboration is two people seeing the third thing. So if you never saw that, if you never saw what I was seeing, then the show would've never happened.

SR I remember coming to your apartment on the Lower East Side and seeing three different rooms, completely different worlds. And I think one was like your yoga room, one was your painting room, and I think you would draw every morning in the yoga room. Do you still draw every day?

KM No. You know what? That's interesting. Well, I drew yesterday, I drew these things.

SR I mean, you use your hand to make marks every day. <Laugh>

KM Yeah, I do actually. Even though I write some off as like, I'm just writing, doing this cartoon note to myself. But I made this funny system up that every day I wanted to do something active, creative, and constructive. So I would do something physical, be in my body, then do something creative and then write, pay a bill or write a letter or clean the apartment. So every day had these three elements that would rotate in and out. And it was that practice of not being stuck in your head, and actually, the three of them are very similar, like doing something physical leads to this feeling of cleaning out your body. And then I can think, and I do some drawing, which would make me able to do something constructive because I was free of these burdens. So it was like a system of unburdening myself, but also making enough "heat," because making something is like friction. So I would always wanna see what I would do every day—because every day you're different and your whole physiology is different. So by making something, it sort of gives you a mirror onto what your body or your physiology is in that moment. So I thought that was not very judgmental, but almost like a phenomena of what we can do every day without being too weighted down with the concept of something. Like just flip it, just do it.

SR It makes me think a lot about the drawings you were making then. And you did have a practice of drawing every single day.

KM Oh yeah, you wanna hear something strange? So this wall reminds me so much of the show I had in your space.

SR I love it. That's beautiful.

KM I know. I've been taking all of these types of drawings that I've been doing and this is an old one.

SR For people listening, your wall in your studio is painted black. And then you've got all this writing and white chalk everywhere. And then you framed these smaller works and they're floating on the space. They're gorgeous—line drawings, paintings. What a beautiful installation you've made. I love how that works together because that's everything. Well, there's more to you than that, but that's part of it.

KM:

This happened—well I did the wall. I was doing the history of the world, like the beginning and the end. And I was gonna do this in my brother's—he's a reverend, so he had this huge church ceiling. So I was gonna do the history of the world, but they sold the building. So I have this sketch for that. And then it looked too flat. So I started putting these up yesterday and I thought, "This reminds me of your show because everything is—

SR Floating in space.

KM:

Yeah. Everything is floating. The black is the empty space. It's like your space and then all the words are telling the story and then all of these are in the void space. And it's strange. I thought, "This is really bizarre." It's like 25 years.

SR Oh. That's nothing in time.

KM It's nothing.

SR I wanna look at that one right behind you with the red and the blue and the white.

Is it a physical drawing or is it a print?

KM Yeah, it's a physical drawing. So I got sick of black and white in the fall, so I bought all of this pastel paper, so it's pre-colored and it has a white frame around it. And I also miss color and I miss painting.

SR They're so good. I saw that stack and I'm like, "Okay, now I have to start a gallery so we can do a show again."

KM I know. Because otherwise I can't get a show.

SR No, you're my favorite artist. We have to do a show. Let's do a show here. Tell me about what is happening in your mind Katie Mertz. What are you thinking about?

KM You know, I think it's, it's ordering. Like these, when I did these every day I would start with one vertical line. And so that's the spine or that's the ordering of the paper. And then from then on I just gave myself license to go off or go really, really simple or really complicated. Like, this is really colorful, but it was almost like– you know what else I was thinking about? I took violin for eight years when I was a kid and I hated it because it was so disciplined and my parents weren't disciplinarians at all. And I kind of loved it and hated it, but it was such a complex language, and I was super shy, so I wasn't very good at talking, but I think I was better at understanding music, so I remember playing these complex pieces and understanding how many layers of sound that's going on, but also there's just four strings, and then tone and pitch—and a line is like a tone or a pitch or a sound.

So I think a lot of this has to do with the violin, you know, like a note is by itself, but it's always in context with the notes around it, which make the music. So I think the line is never by itself. It's always in a context and then there's color or other lines around it. I had to actually study music like it was a language. So I think that had a lot to do with ordering or making a piece and making it seem like there's dissonance in it. It's not perfect. There's all this dissonance depending on what key it's in. So I think I started to do work that had that as a structure–language and not necessarily visual art per se, somewhere I could go to learn something from.

SR Yeah, I totally get it. Because when I look at your murals, the words to me are kind of marks. I mean, I do read them and I see I get some meaning out of them, but I'm really more absorbing them like a visual language. The lines of the letters and it becomes pattern and material and it communicates on a couple different levels. And then to see your other work layered on top of it makes perfect sense because this is your visual language. So tell me a little bit about those black shapes, the sort of ameobic-looking blobby shapes. That one looks like a comb or like an upside-down creature. Like what are those in your mind? What are you thinking when you're doing those? I like those.

KM I know. I love these. You know what? Okay, Sarah, do you remember at Cooper, there's a graphic design class and you had to use plaka?

SR Yeah.

KM:

You're the only person that I could talk to about this. And we had to cut these very specific shapes, and if you went over the line, it was like curtains. So it reminds me of carving shapes with a paintbrush with black on it because these shapes become such objects when it's just the black. And I think it was just making these beautiful 20th century-like objects—they remind me of fifties modern something or other from my past. But I also think they're kind of benevolent in a way too. They're like modern shapes.

SR:

And also you talk about the void or the negative space—I think they're kind of like an element that became a creature.

KM:

Yeah, a hundred percent. Exactly. Yeah, they are. They're like some shape.

SR:

They come to life. So, and this reminds me of the drawings you were making – they have this kind of journey that they go on, right? Like you start with something and you just keep going and these objects become music or stories unto themselves and it's like total improvisation. I guess that's what all art making is in some respect. Maybe some people are totally planned, but I feel like the drawings have a similar language.

KM:

Yeah, I know it's almost like there's a line that goes through everything, and the line changes character or flattens out or is animated and there are no two things that are alike.

SR:

I'm sharing this image right now of one of your drawings. There's so much space, but I feel like I'm looking at a sculpture.

KM:

Because I'm terrible with physical 3D—I'm so bad with 3D—this is the way I would imagine a thing. Yeah, they are sculpture.

SR:

And like modernist architecture painting, 20th century. I feel like there's an aesthetic that comes through, I think because all that you were exposed to as a kid.

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

Do you think so?

KM:

I look at these, and it just reminds me of Eames (House) and all of the 20th century modernist work, which I grew up looking at.

SR:

Like it's all in your back catalog in your brain.

KM:

Yeah, totally. And I was so struck in LA by actually seeing the Eames House live because—

SR:

Oh, we went there together, didn't we?

KM:

Yeah, yeah.

SR:

That was great.

KM:

Definitely.

SR:

That was so long ago.

KM:

It was!

SR:

That was the first time I ever went to L.A.

KM:

I know. Oh my God.

SR:

It was like 1998 or something. Oh, I love this one. So yeah, you went to the Eames House and that was really profound for you. Me too.

KM:

Yeah. I know.

SR:

In what way for you?

KM:

I remember with your show, there were paintings hung from the ceiling and they were different levels and then they were also kind of hung, suspended in midair next to a wall. Maybe it was inside or next to a bookshelf. So they weren't flattened out onto a wall—it wasn't flat, the whole space wasn't flat. But just the fact that they put a painting hung from the ceiling was like every dimension, every space was democratic. It wasn't. And then to take one of these paintings and get it away from the way we get stuck, how we get stuck looking at stuff. I think they broke it. God, how do we explain the Eames House?

SR:

No, I think democratic is a great word because I've always thought about them as bringing art to the masses. You know, designing their fiberglass chairs so that it could be used in schools and wanting to sell things at a lower price point for everyone instead of making it high art, too out-of-reach and just bringing the appreciation of excellent design to everything, to the world. And also integrating everything into their lives. So they had art, music, that painting hanging in the space, the way the furniture was made out of plywood, or the way couches were made, and the material and the way space could be used— like a living room is for conversing and appreciating art and being with other humans and looking out at nature and it brought the outside in and the inside out. And it was kind of about integrating all these elements. But democratic works because everything was kind of treated equally. They never made the architecture bigger than anyone, which is a typical architectural thing to do. Like make it grandiose, make it like the Guggenheim, a little bit overpowering so your art doesn't feel so great. But they made it functional and beautiful and a perfect backdrop for everything.

KM:

Yeah. You said it so well.

SR:

I mean, I'm just thinking out loud, but in looking at your painting on screen right now, it's similar, like you're thinking about how to organize space, how to interact with these different beautiful objects, but then it's like there are these narratives that flow through and I always loved the fact that you made one of these every single day. Like it was a part of your morning practice and that you were emptying your brain onto the paper and it was like, "Holy shit, look at all that stuff she's got in her brain." That's amazing. I think you're brilliant and everything you do is like that. And then jumping over to the paintings that you're making out in the world right now, which are incredible. They're huge. The size of very large buildings. I think it's so cool to look at all the ways in which you make marks in the world in space.

KM:

I mean, in some ways it's all democratic because it's from giant buildings. Yeah, these marks are like little drawings—if you take five of them and overlay them and they're one of my 20th-century type drawings. You know what's interesting, Sarah? All of these shapes and curves and lines that I do, I've done them before in drawings. So in some ways drawing every day was seriously like a practice, like a warm up or they are things in and of themselves—but every shape that is on these buildings, I did already in the drawings—for what, 15 years I was doing a drawing every day. And so I'm quick with them because I've had so much practice doing tiny scale drawings that just blew up into architecture. Which is great because it's like my parents—it's on a building and the building influences the space and people around it, but I have no idea how to build. So it's by default that I'm becoming an architect of sorts with line.

SR:

I feel like the first one I saw was Fenmore Street maybe? Or Williamsburg?

KM:

Oh yeah.

SR:

Was this the first one you did?

KM:

Williamsburg.

SR:

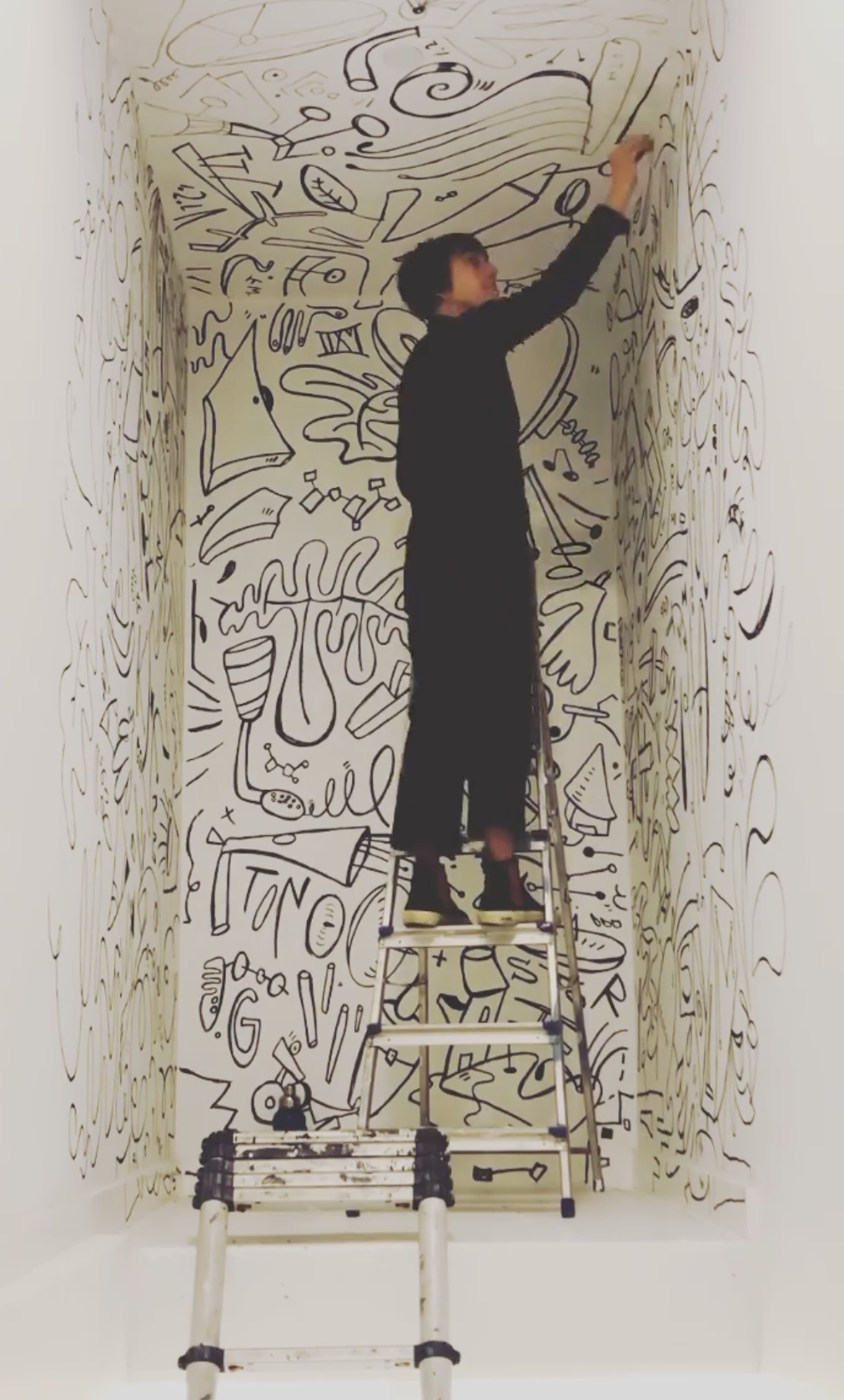

So for those who are listening, you either get invited or you find a project, I'm assuming, where you paint a building black, or a part of it, and then you go— what do you use to paint the white marks? You make all these drawings, hieroglyphs, whatever, I don't know what you call them—is it oil stick, or how do you make them?

KM:

Yeah, it's basic Shiva. Well, they don't make them anymore, but Shiva oil sticks.

SR:

They should make them for you.

KM:

I tried to get them to do that and it was–

SR:

Katie Merz Oil Sticks!

KM:

They wouldn't though, I called the company that would make them for Shiva, and now I just buy the company's very industrial pipeline markers. Like you can mark a pipeline. So they're less oily, but they're pretty good.

SR:

It's just so immense, I can barely conceive of it, but also, you have a background in street art and so you want to be out in the world and you're a life-long Brooklynite, so it's so easy for you to talk with people and you want to create a community around your work, I assume. So tell me, what is it like to go and do one of these projects?

KM:

You know, I was just telling Ty the other day, I am the polar opposite of the person I was when I was a kid or younger because I was so shy and internal and frightened and I really did think something was wrong with me. And I didn't really figure out how other people, like how did they learn to be social? I thought I missed out on some instructional. So after doing so much studio work, I mean your show was like a first, it was almost an inside-outside show, so it was almost public. It was almost more like a public piece because the front door would roll up.

SR:

Yeah, it was a big garage space and the doors were totally wide open. People would just wander in and there would be like the concrete of the sidewalk and then the paper of the gallery and they would just transition into your world.

KM:

Yeah. That was amazing, the way it was an open invitation. It wasn't like white walls, or like, "You don't get this so don't even come in."

SR:

There was no booth that I was hiding behind in the back glaring at you as you entered. I was actually making coffee and offering it to anybody who would come in.

KM:

I know. And I think your dog was floating around.

SR:

My dog was not so friendly though.

KM:

I know. That was, just the whole spirit of it was a precursor to this in a nutshell.

SR:

Interesting.

KM:

Because people were lighter, there was more of just looking and enjoying that they were walking into a garden or something. I mean I always thought that show was like a garden.

SR:

It was because you had clay on the floor. You created these little installations in various places that were sculptural. It was great.

So what's it like when you make these drawings on the buildings? I mean they're huge. They're absolutely huge. The one on Flatbush is enormous. It just blows my mind. It's so impressive that you do this, but what's it like for you?

KM:

Well, I think the first one I was so—this scared part is really gigantic because it was all real. I'd never done that before. I mean, I'd worked for people doing interior painting for years, but I had never done something on the outside of somebody's building and they didn't know what I was gonna do. They just knew it was black and white. Black and white. So the first project I had such a bad stomach, I was a wreck, it was so scary. And every day I would do a foot square of drawing. I was so slow and because I was so unsure and I was under a scaffold too, so I couldn't step back.

And I had my friend Derek read to me, so he was gonna be my assistant, but he didn't draw or trace very well, so he just sat there and read to me. So when he was reading, I would take what he was saying and put it onto the building, which made it a lot more relaxing. Like, take words. But when they took down the scaffold on Williamsburg, I was like, "Holy shit, it worked." And I asked Matt, I said, "Matt, what if this had been ugly?" And he goes, "Oh, we would've just painted it over." But they were so casual about it, they're like, "Do anything you want." And they're developers, which is really not normal for high-end developers. But they were incredibly sweet and they trusted me. But it took a stress toll because I was doing it by myself and I'd never worked that big in my life.

And then after that I was searching for the wave. I wanted another one and another one and another one. Because it was such a thrill seeing a building transform through line, without punching into its surface. So I started getting kind of addicted, like a surfer. Like I just wanted to see what the next one would look like. And then, in Williamsburg when they took the scaffold off, I did the ground floor and people started stopping by and that was thrilling because then I would talk and they would tell me what they saw in it. And then they said, "Hey, can you put this in and this and that." So I started hearing from people while I was working what their experience of it was. So it started becoming exciting in that way. I wasn't just working in a void.

SR:

Yeah. And on Instagram, you share these photos of people that stop by and sometimes you draw something for them or they are interacting with it and it just becomes such a community experience and it's hilarious. All the characters.

KM:

It's so hilarious. I mean when I did this, it was the scariest thing I've ever done in my life. Because I really had never—I took on 9,000 square feet and it was also at that time—

SR:

You mean like the building at 80 Flatbush?

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

That was huge. I was in New York when it was there. It was like two, three city buildings in a row. It was so big.

KM:

Exactly.

SR:

What the hell? How could you possibly do this? You're insane. It's amazing. I don't understand.

KM:

I don't know. You know what freaked me out, flipped me out most? Looking back at it is the scale change because it got bigger as it went higher, the scale. I didn't know how I measured, but I kept saying I'm measuring with my body, because I know in the Renaissance they would measure with their bodies, like the architects, how scale worked. They didn't have super laser measurement. So I lifted up the scale floor by floor and luckily it all worked out.

SR:

Whoa. So you would make it bigger as you got up higher?

KM:

Yeah. So on the top floor, one hieroglyph was like two feet fat and I had to make the line, I draw the line and make the line really fat. So, I'd make completely wacky (designs), like a tape recorder and a boom box, and make these huge objects up there. But it had a taper down to the bottom.

SR:

Ah, got it. Because when you're down on the street, you see them at your eye level.

KM:

Exactly.

SR:

They were that small up top, you wouldn't see it. So it's really for the people.

KM:

Yeah, so if you're across the street, the top floor is the same as the bottom floor and is on the same street.

SR:

How long did it take you to complete the Flatbush mural?

KM:

A month.

SR:

Unbelievable. I mean, it looks like three years of work. It's so many drawings. Like you covered every inch of that building with your hand.

KM:

You know, the thing about this process is I feel like I'm writing. So I would draw the main line, the white line of the drawing. So I don't have paint, I'm not filling in and I'm not pre-planning everything. So I am absolutely in the moment just moving forward. Like either moving up or left or right. So it's a faster process than you'd think.

SR:

Okay. But it's a download from you, right? Like It's coming out of your mind and your body. And it's a conversation that you're having. I mean, everything in here is a symbol, a shape, an idea. They're all conversing. It's sort of like a puzzle.

KM:

Well, it's actually made like a puzzle. You're right. The conversation that I have in my mind when I'm making this is so I put a shape up, say like a cent sign and then I think of what's like free association. Like what could go next to that? What in Brooklyn is over here, what building, a stoop? When I was growing up, the whole idea of the surrealists was really—their activity physically and mentally was like extreme sports. So automatic writing was really exercising the imagination. So when I start drawing, it's a similar exercise where I at that moment have to come up with something that references the last thing I drew and then I'll have a judgment. Like, "I don't like it, it's ugly, too small." So that will also prompt me to do a different shape with a different character, with a different meaning. So I'll keep adding, but my mind will have gone in a different direction.

So it's almost like a sports feat. I always think it's like extreme sports. My mind has to keep moving past what I've just done. And it is like a download. It's like, "Oh shit, what, what is this? What is that? What's the next thing? What is the next word? What?" And "What shape should it be, three-dimensional or flat?" or, "Is it a word, a number, an object, a building?" So I guess it is like problem-solving or like making a problem for myself to solve.

SR:

It's just so endless though. What keeps you going? Like you must have some positive mantra that just keeps you from thinking "I'm exhausted," or I don't know. You seem to have some methodology that gets you past that, maybe you subconsciously developed it. Or are you conscious of anything that keeps you going or keeps you motivated?

KM:

You know, the odd thing is, I don't get tired when I do this at all. I get weary. Because I remember being on this building and Tyler was like, "You gotta go home because you're not drawing anymore." So I would go back, but I don't, I love doing it so much. And I feel like, what happened? Last I looked, I was just in my studio quietly by myself struggling with who will ever see my work. And now I'm so grateful to be doing this.

SR:

You're out in the world doing your painting.

KM:

Exactly. I don't want to stop. And it's so much fun.

SR:

That's awesome. And people love it. There's so much reciprocal joy that it creates.

KM:

Oh, that's good.

SR:

I gotta give a shout-out to Tigey, your dog. That girl is so powerful. She's the queen of Brooklyn.

KM:

She is.

SR:

Rest in peace Tigey.

KM:

She would just lie there and her belly was shaved because she had some operation or something and people would just step around her like to give her loud space.

And the fact that I was on the street drawing, people would always come up to me and I thought, "Of course I'm going to—I made the promise to engage everybody that stopped me. I'm not just drawing past people. I'm drawing and I'm stopping." And that's when I started doing the cartoons. Putting people in cartoons. Because I'd say, "What are you, what are you thinking? What do you want to be, what you know, what objects?" They'd start talking to me, and that way I would draw them into, almost like the beginning of the camera. I would draw them into this scenario and they would get such a kick out of it. And then I would send it to them. So they'd have, I guess not ownership, but they'd also yell up and tell me to put this on and put this building up and put my friend's name up so everyone kind of had a piece of it as theirs.

SR:

Yeah.

KM:

Because you know, I mean I'm so anti-exclusive art. I just find that it's the antithesis of what the word means.

SR:

Yeah.

KM:

So it was just really amazing to engage people and have them feel like part of it. Even if it was for 10 minutes.

SR:

So people would sometimes come and perform too.

KM:

Oh listen, every day.

SR:

Everyone wants to perform. You gave them a stage.

KM:

Everybody wants to perform. Especially in New York. Yeah, you're right. Everybody wanted to perform. I'd spend half the time drawing these things and when I was up on the scaffold, I think I actually took a break from the people. I could work a lot faster.

SR:

And I'm just thinking, what is your trajectory? What are you working on now? You got some big projects. You have done so many buildings around the world and I bet you're getting more. You also do interiors and you're collaborating. You've made some products like painting on shoes, painting on clothes. Like what do you want to do actually? What's your next dream activity besides a show in my gallery?

KM:

Yeah. Your gallery. I want to do something in Europe in a beautiful small classical building in Berlin or something. I would think it would be because this is so familiar to me, Brooklyn. But some floor or ceiling, like an asphalt floor or a ceiling. Or an all encompassed space somewhere where you're in the drawing, you're in the entire thing. Instead of looking, it's like Flatbush. You could look at this entire thing. But I would love to have something where your whole body's in it.

SR:

Well the most recent one that you did in Lisbon feels a little bit like that.

KM:

Yeah, exactly. That was close. And then I did one in Arkansas at the Bentonville Crystal Bridges with blue and red benches. And then, oh they want me to come back and do a water tank and then a building. So it's almost kind of experiential in that way because you're eating off the tables and then you're in front of the building. So it's like a public version of that. And then in July, I'm gonna do a corn silo at this artist residency where this all started. So he found me a silo out there. So we'll see.

SR:

What's it called?

KM:

It's called the art farm. It's very shaggy. It's very raggedy, but you can do anything on any building out there. And that's where my first roofing paper situation was where I drew on roofing paper because there was a roll of it out there and I tacked it to the side of a barn. And that was like my first realization like, "Oh god, language can be on architecture."

SR:

Yeah. And you called it hieroglyphs in the beginning, right? I remember seeing that.

KM:

Yeah. Like translations of words.

SR:

I wonder if you've thought about making sculptures yourself—I know you said you don't want to make architecture or you don't know if you could, but I might imagine a room that you could inhabit or a sculpture that you draw on.

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

Like if you could make your own object, I wonder what it would look like?

KM:

Probably would be like the drawings where it would be a different character altogether.

SR:

Yeah. Like one of those blobs.

KM:

Yeah, exactly. Like a clay blob that's colored.

SR:

A black or colored blob.

KM:

Like put a little piece of my drawing into it, blown up. And then three dimensionalized.

SR:

Just to be totally frank—so people in the art world might relate to this work on buildings as some sort of commercial thing that they would then say like, "Oh that's not real art." Or like what they might say about street art—I don't feel that at all, but I just want to put that out there as a subject to consider. Like for me this work is a continuation of everything you've ever done. Like you said you were doing these drawings, warming up for 15, 20 years and here you are working in three dimensions, making flat two-dimensional drawings, but working on three-dimensional spaces in public. I mean, it's transformative. It's connecting to so many people and it's gorgeous, but there's so much to decipher. It's so complex. I feel like just this one close up we could look at for an hour and talk. And then a lot of times it gets painted over or torn down. In the case of Flatbush, the whole building got taken down.

KM:

Yeah, I know. I knew that when I was getting into it.

SR:

There's this impermanence to it, which is really bold that you're just willing to do it for the moment. To be in the moment.

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

That you just bypass the art world. You're like, "Screw you guys, I'm going to do something that people can actually use and feel and be in the world." Like there is this frustration of being an artist and never really connecting to your audience, or never having the opportunity to show. You're like, "I've got so much good art in my studio, how do I get it out into the world?" And the internet is a great help, but getting it into a gallery is not necessarily getting it into the world.

KM:

Yeah. It's ironic though because it is that world and that world counts for something.

SR:

Well traditionally, that felt like a validation, but I don't think you need it. In our minds sometimes we're like, "Oh, we want to do this," but I remember talking to you five years ago and you're like, "I just hit my stride."

KM:

I know. Late, late stride, I didn't give up.

SR:

Then you get so much energy from it because it's so in line with what you're supposed to be doing.

KM:

Yeah, that's true. Exactly. I mean with the gallery, when I was making this wall, I thought, "Oh, I have these framed pieces. I have the colored pieces on pastel paper and these wheat paste legs." And this would be kind of an interesting show because it's like yours. It's all these layers and everybody gets what they want, or it's this multi-dimensional situation and it could work in a gallery. But then someone said, "Well why don't you make a show?" And I thought, "You have no idea what that simple question entails."

SR:

I think you're such an amazing artist, so I'm glad you never gave up and I'm glad you found your stride. But I still could see all of this work in a gallery. I do think that it is complex and even though you use cartoon and even though you use what looks like white chalk and they are line drawings, it is complex. You have this very intricate language. Like I'm looking at this image right now. Were you drawing on black sheets of tar paper or just black paper?

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

And there are all these symbols.

KM:

Yeah. I had six pieces, six pages of this woman's poetry and I broke it down into hieroglyphs. So I took all of her work and made it into symbols.

SR:

Well that's really interesting. So it's kind of like when your assistant was reading a book to you while you drew.

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

It's like giving your mind input and then translating through your lens and hand.

KM:

Yeah, exactly.

SR:

And you're going fast, right? So speed is a part of the challenge.

KM:

Yeah, it's true. It's like the next thought, the next thought, the next thought or the next–on some, I have to make this long list of words and then I riff off of that so I don't start getting exhausted with having to come up with something.

Oh, that's the piece. That's the first piece I did. And that's the roofing paper on the wall, that's the art farm.

SR:

2015.

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

Oh cool. So it's based on a poem by Rilke?

KM:

Yeah. He's easy, his words are so beautiful and spare. There's like space around his words. So it was easy to take a thought of his and break it down again into what I thought were symbols that represented his thought.

SR:

Yeah. This one is actually more intricate than your following ones. It's like you got speedier or like shorthand. This is obviously more narrative and the other one is more immersive. You're in it.

KM:

Yeah, exactly.

SR:

And in your drawings, I was just thinking about words because one of the drawings that you gave me has words, it's a poem. So you talk a lot about writing and what else can you say about that from when you started? Here's one with writing.

KM:

Yeah. It's a similar structure as when someone's reading to me, when I'm doing a building, I feel like language immediately breaks down into image imagery.

SR:

Here's one.

KM:

Yeah. Oh, that was like a frame.

SR:

It's like writing around the edge of a painting. But cartooning, writing, music – kind of stream-of-consciousness, daily practice, all these things have been a part of you for so long. I feel like they kind of seep through and you've created a language and a practice out of it.

KM:

You know, I always feel very undeserving like I'm just doing this stuff and our brains have so much energy to burn and I think this is a very non-harmful way of burning that energy. We just have such an amazing amount of creativity and curiosity in our minds that we're lucky to have so many outlets and I feel just very happy that there are outlets. Because God knows, if I didn't have this or if I lived a hundred years ago, 50 years ago, I would be in really bad shape.

SR:

Yeah. I feel like you have a PhD in creativity and improvisation and you've just had this incredible practice of letting it flow out of you. Like the point of this drawing was not to make a composition. Right?

KM:

Right.

SR:

That is not what you were thinking. Like, "Oh, let me make a painting that people are gonna look at." You were thinking something totally different.

KM:

Yeah. It's like an introvert’s conversation.

SR:

With yourself?

KM:

Yeah. Because I was so shy and thought I was dumb and all of these things. And so because I had these visual-to-visual conversations with myself that didn't really translate to the real world, I was like, "I am going to develop that language," because that's what I know and this other stuff I maybe will work into later, but it was like survival, of making your own language so you don't feel completely marginalized as a human being.

SR:

You created a practice around your needs, but then you also allowed your brain to just expand and your language of drawing and painting and mark-making just grew and grew and grew. I mean, you've really developed this practice over a very long period of time. And it's beautiful. Like, I love this image that we're looking at right now. It's like painting and drawing and it's a three-dimensional world and it's very sculptural. I've always wanted to figure out—there's probably is now with video and AI—but some way to take an image and float inside of it.

KM:

I know!

SR:

And I feel like that's what your work does and that's what you liked about the installation. It's like, "Here's what I have in my brain. Do you wanna go inside and check it out and float around?"

KM:

Yeah, when you asked me what the next thing would be, I would be like, "That." But not just black and white. Just all like going from one–

SR:

Immersive world.

KM:

Yeah. Just having you in there.

SR:

But this painting that you made, if you could go like 10 feet inside of that painting and float in between these two spaces or something, that would be so beautiful. It's so interesting and sort of non-architectural, like the kinds of shapes that you're working with are not the building. In case anyone doesn't know your background, both your parents were architects, they made really incredible work in Brooklyn and you grew up around that.

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

And so you had to find your own language or your own language came forth in like, how do you understand the world? What kind of shapes are you gonna make?

KM:

You know, what I realize when you're saying that is that they built the house that we grew up in, so I didn't realize this till later, but I grew up in their mind because that house was like a square. And everything that was in that house was from their ideas. Like, we're gonna have this thing be this tall and the handle's gonna be here and we're gonna have the sliding doors and here's how you enter the living room. And this is the quarry tile floor. So everything was their mind, like they had planned it out and then what colors or objects were in there. So in some ways being brought into their creation–and it kept changing over the years.

Like they'd renovate it or put windows in here and change the staircase—it was always changing, but it was always their creation and that was so giant. And they'd have the office on the top floor, where I would see them drawing. So I think that was where the brain was, was the office on the top floor. And they were so much fun and very casual. So it wasn't very serious, like, "I'm going to the office." They would just go upstairs. And so I think part of it is that I like having fun when I'm making work. I mean, you're doing it so it's a serious practice or it's an intentional practice, but I think they weren't so serious. So I think it was easy for me to keep making because the making was the important stuff, not so much thinking, "Is this perfect?"

SR:

It was the daily practice that they instilled in you. Just making is important.

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

It's a part of being, but also I wonder about the walls. So the walls of the gallery can be kind of oppressive. This white box and then the walls of the home that you grew up in. And I think a little bit, perhaps that's why you're working on the outside of architecture out in Brooklyn and in the world. You find these incredible towers and things to make your marks on. But you're building on top of something that's already there. There's this layer, you're not so concerned with creating a structure to put bodies in, but you're like, "How can we bring the visual narrative out, like an overlay?"

KM:

Yeah.

SR:

Almost like the skin of the architecture. Like you're trying to get to the outside of the box. And so being in the gallery is not exactly your natural environment. It's not dynamic enough.

KM:

Yeah. Right. It's so controlled. It's like these paintings are up and they're good or they're not. And you have to stand in front of this or you have to observe it and think this, and this person's got a good review. And so with that, it all feels very doctored and controlled. It's too bad because there's no way to see these unless they're in a gallery or they're online. That's good enough. But there's such a restrictive culture around the white, the box, and the control of the gallery system.

SR:

Yeah. And that's what I liked about this show we did together is that there was this freedom and you had these bins of photographs, like thousands of photographs that you had made and they were small 5X7 and they were in the bin and people could sit down. You had a chair or a little ottoman—

KM:

Medicine ball.

SR:

Sit down on the medicine ball and look through all the photographs. So there was this interaction and people could pick out what they liked and it just was not so precious.

KM:

Yeah. Oh my god. That was my mom's coffee table that she built, that low white table. I remember I was bringing in furniture from my apartment.

SR:

Yeah.

KM:

That show was the best.

SR:

Yeah. I'll find photos of it.

But I wonder where your conversation is going next?

KM:

Yeah, that's a good question because I wanted to go to the farm because that's where it all started, but I didn't wanna be manically repeating myself and getting another building if it doesn't have a certain kind of meaning to me. So I figured I'd go to the farm and go back to square one and I'll have a silo to do, but I also wanted to work there and in freedom, just to see what would be next or what is interesting to me next.

SR:

Yeah.

KM:

I don't know, I was gonna write a little cartoon history of growing up in Brooklyn in the sixties.

SR:

Oh, that's a good one.

KM:

Like a collage thing, but because the last time I was there I did sneakers and I made a silk screen, I was drawing on train cars, I was doing everything to find out what stuck. And I think I'm gonna go back out there and do the same thing. Just start from scratch and see what's compelling or what I haven't done yet that I don't even know is in there. Because I don't wanna get stale.

SR:

I don't think it's possible for you to get stale. I wouldn't worry about that, but I think what's on the wall in your studio is really cool because everything's playing off of it, off of each other.

KM:

Yeah. I feel like I'm repeating myself, but it's so much like your show where it's not the one thing, it's all the things together.

SR:

That makes it kind of sing, like then you see all the elements of your thought process.

KM:

Yeah. I mean, and also, I always think shows that show process are really fascinating to me because when you just show the finalized part, you don't get to see this process that we go through, which I think is phenomenal. Like the thought process and the way you change your mind and shift something and then you eliminate something that is so phenomenal to me. And that's what I miss in galleries, or even in anything, the whole process of making is really a phenomena. It's like this human being phenomena, the making process. It's not about the product as much. So maybe the buildings and the walls are like, okay, this is part of the phenomena of what we all do every day, this thought process.

SR:

And like you said, we change every day. We're different every day.

KM:

Yeah. I remember when I took yoga, the first yoga sutra is basically translated into watching the fluctuations of the mind, which is constant. We're always changing. Our mind is always changing and just watching that is fascinating. Or it's not like we need it to not change. It will change. And it is changing. So in some ways, making things is like observing the constant change of your mind by somehow expressing that.

SR:

Yeah. Well said. It's beautiful to think about how you've developed this practice in order to be able to do that. And you've done so many residencies too, where I think you give yourself this time to go away and just check in. It sounds like, "Where am I at? What could I do now?" Like, not getting in a rut, but always reinventing, digging a little deeper into what's interesting to you. And being around other people too—does that feel like it activates something for you? Or the residency is giving you the assignment?

KM:

Yeah, I just got back from Carriacou down in the island for three weeks. I kept staying. I didn't wanna come back because I just wanted to empty out—cause it gets very manic in New York and you're like filling, filling up, filling up, doing, doing, and it just becomes almost habitual. But I wanted to completely not feel like the habit or the compulsion to do so. And then everything gets really simple. Like, oh my God, I'm just going to draw on the sidewalk with chalk or it just goes back to the basic simple elements of making somebody something for something. If it doesn't go back to a basic state for me, then it becomes like a compulsive state of making, which is not creative.

SR:

Yeah. One of my favorite projects that you did was when you got stuck on an island during Covid and you started making drawings on the sidewalk with children and a goat and it was so amazing how you made such incredible stuff out of nothing and you just took what there was and started to converse with it. It was so fun. It was like, I knew you were feeling trapped, but you were also, given the parameters, you were able to just go crazy.

KM:

Yeah, that's where I just came back from. That is my favorite place on Earth. Carriacou. It's very, very, very far in the ocean away from Grenada. And it's so simple. It's so great. And you know, I couldn't even find a Sharpie there. This last time I was there I couldn't even find chalk. It's really up to whatever's there.

SR:

So you were lucky you found chalk the first time?

KM:

Yeah, I guess it's been used up in three years. I dunno where, but I brought some down with me, big pieces, but I ended up doing like a sign in someone's store and now I'm gonna do her church when I go back. But I thought I would do chalk drawings again this time, but it seemed forced. So I thought I'm just going to do the next thing, which is I started making friends and doing stuff for other people, like a picnic table. And then I did the store. So I wanted to repeat the chalk, but it wasn't the same time or the same place or the same world. So it didn't work, which I have to respect that things change and I can't control that either.

SR:

Yeah. I know the passage of time and you're not where you were. I mean, that was a really unique time.

KM:

Yeah. You know, I think all of the pieces that I do, like Flatbush, could never have happened now. They wouldn't have made it a commission. They wouldn't have picked me. Every single thing about that project would not happen now. And the school that asked me to do the smoke stack when I went there last year, she said, "You know, it's amazing we got that through because that wouldn't have happened now." So I think I'm constantly getting the last second that something can happen. And I think in some ways that makes it special because two months later it wouldn't have happened.

SR:

Well I think they were meant to be so they happened when they were supposed to happen, you know? And this has been like a really intense period of like five or seven years of you doing nonstop paintings on buildings, right?

KM:

Yeah. It's intense. It started to get intense. Like that's why I had to go away for three weeks and do nothing, just being on the island in nature. But yeah, I just started losing touch with why I was doing it because it was like I was being pushed through this portal and all this work came out and now I'm out here and I wanna know what it's like, what's on this side of it.

SR:

Yeah. Well I can't wait to see, I'm your biggest fan.

KM:

Maybe it'll be in Sarah's gallery.

SR:

I'm gonna put it on some website, whether it's in a physical space or not, it's gonna exist. It's so great to talk with you Katie.

KM:

I know. I was looking forward to this my whole day.

SR:

Aw. Well thank you so much.

KM:

Thank you so much Sarah. This is really an honor and I find it amazing that you wanna hear and you listen and I just find the whole thing kind of great that you're doing this.