Inside Art Episode 3: Millie Benson

Published:

April 24, 2023

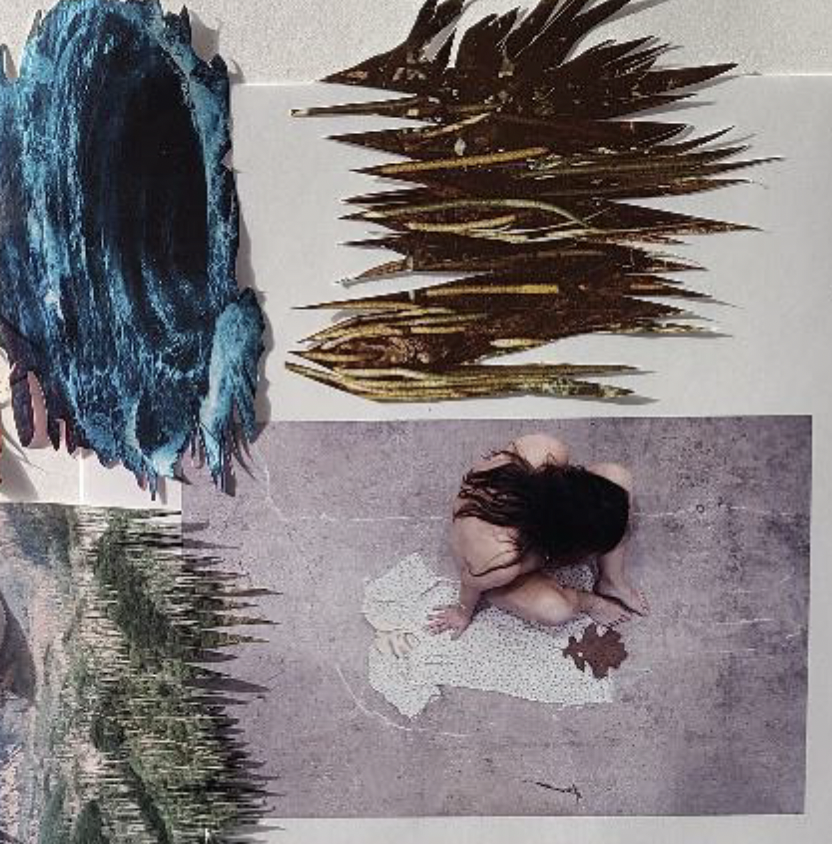

Artist Millie Benson makes work that develops in a poetic and slow process, mapping the passage of time, collaging found images, and then photographing her body with a collection of natural objects.

In this episode I speak with Brooklyn based artist Millie Benson. She makes abstract paintings and poetic photography. We talk about an in between space, of not knowing what something will become when you’re in process, and ultimately the transformation that is possible through art making.

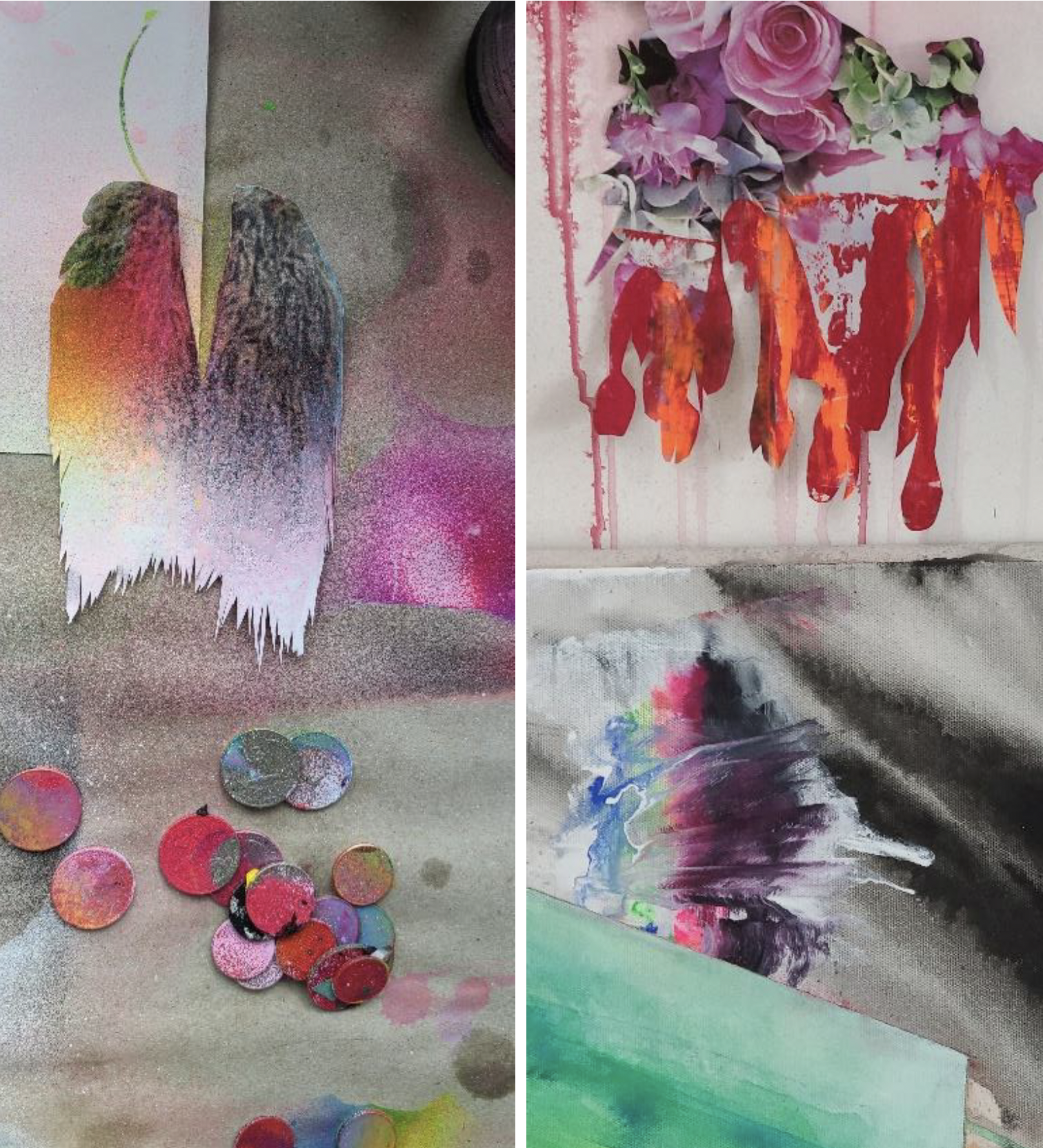

Millie shares some recent photographic work using her body and a collage of objects found in nature, as well as mini brightly colored paintings she made during the pandemic. Cycles of loss and rebirth inform her work as she reflects on the experience of being in isolation and coming together again.

Listen on Apple, Spotify, Amazon Music, Google Podcasts or wherever you listen to your podcasts.

“Sometimes I’ll just lay out a white piece of paper and get onto the paper just to put myself into the work.”

Video Highlight

Inside Art Episode 3: Millie Benson, 15 min video clip

About Millie

Millie Benson is Brooklyn based artist. Her paintings and photographs have been shown throughout the United States and internationally. She moves fluidly between mediums and methodology, from working with light and found objects, to composing photographs and collages, to abstract painting.

Benson has an extensive background in working with private art collections, and is currently a senior advisor to a private charitable foundation in New York City. In addition, she has curated art shows and hosted projects at her studio space in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, exploring the creative process with other artists and makers.

Website: milliebenson.com

Instagram: @milliebenson

Please rate and review this podcast on Apple Podcasts

Thank you for your support, it helps share the podcast with a larger audience.

Transcript: Inside Art Podcast, Episode 3 with Millie Benson

Sarah Rossiter Welcome Millie Benson to Inside Art Podcast. I'm really excited you're here, and I'd love to hear how you're doing. I know you're in Brooklyn, New York, where we met about four years ago.

Millie Benson Well, thank you for having me. I really was looking forward to doing this. And, yeah, I'm in my studio in Brooklyn. All is well.

SR You have an incredible studio. So I almost rented your studio upstairs from you four years ago. And I, you were the first artist I met there at your open studio, and I walked in your door and I was just blown away at your work. And you had it all spread out, photographs on the table, paintings on the wall, your guitar probably in the corner in these amazing windows that face the Hudson River or some buildings in that direction.

MB Yeah, I face downtown New York City. And I get the Hudson River School light.

SR The other thing that I noticed about you is that you are very collaborative and you have events in your space, and you bring in other artists, and you're a musician. And you do painting and photography. So this really appeals to me, your diverse practice. Do you want to talk about what you're up to now? You have a new body of work behind you there.

MB I do. Maybe I'll just start by saying that I did rent this space the year of the pandemic. I participated in an open house in New York. And then I had a couple of gatherings where we made some art here. And the pandemic happened and then the Navy yard closed, and I was working at home in, in my bedroom, on my bed on these little teeny paintings which I haven't done in years. And then, so that was a big thing that I, part of the reason I rented the space was to share it with people and have events. And then the pandemic happened.

SR And it was actually kind of shocking at the time I was there in the same building with you, and it was like, we went from normal life and ready to do shows and connect, and then suddenly buildings are shut down. You know, schools are shut down. Everything is in lockdown, and thousands of people are dying at the hospital down the street, there's the morgue truck. Like, it was really scary. Yeah. And we didn't know what it was like, we didn't know if we could be in the building and go into the public restroom. You have to take an elevator. So you were really courageous, you stayed in New York. I fled. And I'm really glad that you were telling me before like, in a way the pandemic did you a favor.

MB I was very lucky in that, in my day job I was able to work remotely, so it gave me the— I guess I would say maybe two and a half hours a day that I would spend commuting. I was able to just sit and paint after work.

SR Wow.

MB Yeah. So I have to tell you... when you asked me to do this, something just came to my mind right away. I tried to look at some other things, but this just came to my mind. So I'm doing this, I'm gonna talk about this with you, and haven't talked about this or shared this work with anyone.

SR Oh, I'm honored. Thank you.

MB So, not this Christmas, but the Christmas before that holiday we went to Boston to visit my husband's parents, and it was the first time since the pandemic happened that I had been out in the world, like really out in the world. And it was such a joy to be in the, to be in the same house with the grandparents and like, to just be like, just be back with people.

SR Humaning, yes.

MB It just, it really struck me. And I think that at that time, I realized how much the pandemic had actually affected me. So anyway, I came back. It always, on the first of the year, I'm always just like, oh my God. Like, where, where am I at with things with my work? A lot of times like, I'll come to the studio and I don't have any idea. So I took these photographs. I came into the studio and I was like, I really want to, like, lay on the floor.

It's this cement floor in here, it's a big white rectangle. The sky is right there. And sometimes it just feels like I'm on a spaceship in a way. So, a lot of times I'll bring things up here that I find in nature because I feel like I'm really up here in a sterilized-like place. So I took these photographs. I was feeling, I'll be honest, I was just feeling really bad, basically, like sad, like grief. I had friends that died in the pandemic, and I had just found out about a good friend who had passed away. And so I took these photographs. Sometimes I'll just lay out a white piece of paper and get onto the paper just to put myself into the work.

SR That's beautiful. Actually, put your body on the paper. That's brilliant.

MB Yeah. Because I feel like a lot of times when I'm in front of the canvas or in front of the camera, I don't want to say it's like a mirror, but it's like a portal or it's like a space that reflects a little more of what's going on than what I might actually visually see. So I put the paper down and I'm always thinking about aging and memory when I'm doing this. So, I had some stuff. So the next picture is just I had, I collect like all these things from outside, like just deer skulls and shells just whatever but I had these hunks of white clay that I had collected from somewhere. And so I got one of those out. And then I had been collecting leaves all fall and I kept being drawn to these leaves that had these holes in them that like lace. There are also shells that have this lace, these little circles. And I had been painting little circles and planets and little dots. So I think that's why I was so attracted to these leaves.

SR If you want, I can share my screen while you talk

MB Oh, yeah, sure. Yes, so that's the first one on paper. And then the second one is the clay. And then, there's one of just the leaves, the third one down. And then I started thinking about how different everything is. And people were saying things like, oh, before times, like before the pandemic. And I have all these old clothes in my space, so I had this dress, this dress was from when I was so young and just a totally different body, a totally different time period. And I just like, kind of was like, I want to go back, but I really can't. And this whole thing has changed the world. And so I was like, thinking about that. And just sort of like trying to reach back and then realizing like, well, you can never reach back.

So, I have these tables that I just lay all this stuff out on. So there were weaves and shells and bird feathers. It's all found stuff. None of it is purchased. During the pandemic, we took a trip, we went to Montauk and we went to that beach that has the Purple Sand, I think it's called Ditch Plains. And it was the dead of winter. And I was standing there and I, all of a sudden I looked around, I realized the whole beach was purple, and it blew my mind. It completely blew my mind.

So I spent the next three days photographing this purple sand and all the images are up on my Instagram.

In this picture, there's all this purple sand. I brought some back in these little shells because I wanted to put it in a painting. So these were just like, all the things that I was thinking about. Yeah, that's the Purple Sand. I mean, look at that.

SR That's crazy.

MB It's crazy. And I don't know if it was more purple, maybe there's just more of that mineral. Maybe it was because it was winter and the tide had brought in purple and then it was mixed with the snow that made it lighter. But it was just so striking. And I really, really wanted to dig a hole and get in the sand, but it was so cold. It was really, really cold. And I had on a snowsuit and I head on these big tall, snow slash water boots. So for these pictures, I was able to walk pretty far out into the water actually. Wow. And just kind of like, be standing in this purple world.

SR Oh, that's incredible.

MB It was such a gift to be able to just see it really. The patterns.

SR Reminds me of the work that you did in your studio afterwards. It's sort of like the impression, the memories, the physical sort of little trails of presence.

MB Yeah.

SR Things that have washed away, what's left, these little artifacts.

MB Yeah. And I think the other thing about it that is always so interesting to me is that when you're actually in it, it's constantly changing. And I don't even know if it would've been a different day or if I would've been in a different mood or a different time of the day, I might not even have noticed it. So I came back from that trip and I researched the color purple and I bought all these different purple pigments and just like got into the history of the colored purple.

And then in the studio, this next picture, I would just say that maybe that was the darkest point, was the Montaque trip and the Purple Sand and the coming back from Boston. But the sun kept flooding in here and so I took some pictures.

I started doing some collage work during the pandemic. We were traveling and I kept cutting out these pictures of these little pictures of ghosts, like little shapes that looked like ghosts. And I was like hanging them on the wall. And the sun was coming in.

SR I just want to pause for a second on that one with you and the chair and the sun.

MB Yeah.

SR So the camera is above you and looking down on your naked body, sitting in a chair. But the artwork is behind you on the wall. And it's a really beautiful image. It's very stunning. And it definitely feels sad, but it also has that intensity of the sun. And like, it's so interesting what you're talking about. Like these cutout paper things on the wall have this absence to them. It makes perfect sense what you're processing. And then if you go back to like all these artifacts that you've collected, the leaves, the rocks, the stones, and the like, it's like the body trying to make sense of the environment and the environment informing your processing of all this grief. And you're in an in between phase too, because at that point in time, the pandemic was starting to shift and it's like, it was so hard to be locked up and lose so many people. And then to come back to life, there's this disjointed in between time where you're like...

MB Very disjointed.

How do you go back to just making art? Like, you don't go back to who you were, you definitely are someone else. But like, I feel like it, what I get from these images is this intense feeling of questioning all reality, meaning and impetus. Like what makes you want to make art in the midst of difficulty. And even when it gets better, you know, in our cellular memory we hold on to trauma.

MB Yeah.

SR And it can't just go away without some kind of process or recognition.

MB Yeah.It reminds me of the book, the Body Keeps the Score which I started reading during the pandemic. But, I've actually done a lot of work around that kind of stuff. And so every year at the beginning of the year, I do a body tracing of myself. And usually, I'll have some friends over and we'll trace each other's bodies. So it's kind of hard to see, but right there is my tracing of me in the middle, and then to the right are the leaves. And so we traced our bodies at the beginning of the year. And I had a very old tracing of my body that I did when I was 21.

SR Wow.

MB I was in the desert in Arizona, and I traced my body and then I collaged into my body like into different parts of my body. I made this collage. And when I moved into this studio space, I found that collage, that tracing. And what I did, I don't know why, but I just had to do this. I had this couch bed thing that I have in here that I use. It's like a daybed sort of couch. I laid the tracing on there and I left myself on the couch to watch the sky when I'm not in the studio.

SR Oh, cool.

MB And I, I just felt like I had this, I had this body tracing and I just, I felt like, "Hey, I want to see the sky even when I'm not in there." So every year I do one.

SR That's really beautiful. It makes me think about... you're working with these in-betweens, like between time and between life and death and between the material and your experience of the material. Like, if you're not there but you're tracing is there, are you still experiencing it energetically? It's really cool.

MB Right. Yeah.

SR I love it.

MB Yeah. Because that's something I think about a lot as an artist when I spend so much time standing in front of something and having this conversation with it, is it then a portal? What is it?

SR I think it is, but yeah, it's hard to describe portals because you can put your stuff in it, but you can also receive from it. And I think—

MB Right.

SR As an artist, you're doing so many things at the same time. Like, you're the viewer, you're the creator, you're the meditator, you're the–

MB Yeah.

SR You're creating out of your body memory.

MB Yeah.

SR And that practice of tracing your body every year is so interesting. What got you started doing that?

MB I was just, I was in Arizona in the desert and I was doing a workshop and it was like one of the tools that they had for people to do. They just had stacks of magazines and I was there with people who were not artists. I think I was the only artist there. So mine was super weird. And I was cutting out all these shapes and blobs because it was supposed to be like, how do I feel in my chest? Okay. Well, I feel like very heavy there, so it was like blobs of rocks or—

SR Yeah.

MB I remember there was a lot of water stuff going on in my abdomen. I started cutting into it. I traced a copy of it and then I cut it out. I just started working with it. What happened was then I, it became like a collage explosion and the light.

SR Yeah. So the images of your studio with, for people that aren't looking at this, these long tables with tons of beautiful collage, bright colored stuff that...

MB Like blobs of shapes.

SR You've assembled various… and then the sun is streaming in, and the painting in the background, like it's like a full on workspace. 3D collage almost.

MB Right, right. The sun is really an element in here. It comes in and it lights things up and it makes these shadows. So then the shadows start to make shapes. Then I'm looking for those shapes in the collages and they're coming out in the paintings. So it's like a conversation with the light really.

SR Which is amazing because it's along the same lines as the conversation with the cutout paper and the leaves and the water and the sand. Like they're all natural sort of phenomena that happen with light and with like this material. I love how you're working. I love that it's not really anything too, you're not talking about like a concrete piece, but we're like, in the midst of your practice, it feels really metaphysical and physical and sort of poetic and slow.

MB Yeah. It's very slow.

SR I like that.

MB Way slower than I think that artists work and move or I, anyway, this stuff takes so much time.

SR It also feels like there's not a purpose. Like there's not a goal, like you're open, you don't know what the endpoint is.

MB There's not a goal. The goal, I think the goal only is to just try to get out of the way and sort of just map where I am at any given time or, and sometimes it's not just me, it's like my family or friends or it just, it's more of like a mapping.

SR Yeah.

MB I was so I just, I included a few pictures of the collage shapes just to kind of–

SR These are beautiful. So are they all cutout paper?

MB They're, they're all cut-out paper. Okay. They're all what I started doing… Sometimes when I can't paint, when I'm not ready to paint, I have to do something. So I literally, for like six months. I was just collecting magazines out of the garbage of my apartment building. And each one is a piece of paper that I cut out by hand.

SR I want to just pause you to talk about this part of the image. Do you mind?

MB Yeah.

SR It's your body photographed from above and you're sitting on a concrete floor with that dress from your childhood. And then this leaf, I think this is an incredible image and I can say a lot of things about it, but maybe you want to speak first.

MB These are big by the way. I think the paper is all, it's like three and a half by four and a half feet. They're big. I think I had 10 going. I had 'em on the wall and each one was sort of like a map. I was actually listening to podcasts. I was listening to this podcast called "This is actually happening." It just was so captivating. So I was listening to this podcast and then in between that I was like looking back at these old photographs because this friend of mine who had passed away from Covid and I was trying to find pictures of him.

A lot of my work is about sleeping. It's just, there's always references to dreaming and sleeping. Like the size of the paintings are big like beds. And so I've always loved folded sheets and towels, like in magazines how people style them and make them so beautiful. Like they're a color wheel or, you know, like they're scientific. They become scientific really it was like, here's my towel stacks these like water, these different water imagery things were coming up and there's like a little poofy ghost in there, but it, it's really just like, sort of this one in particular felt to me like a walk through the forest. And just sort of like thinking about the past, but not, not necessarily the future, but some other time. I don't know if the future is always so important to think about, although I do think about it a lot.

SR It feels, again, to me, like you're in the midst of transformation and it's that most uncomfortable time when we don't want to be where we were. But it's this really unpleasant processing of all the confusion in the midst of transformation. And then you would assume that the next experience will be amazing and you'll be in a different place. But that in between places is what this feels like to me with also so many options on which way to go.

But what I really wanted to talk about was the image of you in the corner, that is, it's on its own a photograph too, from your first series that you shared with us.

MB Yeah, yeah.

SR And I feel like in the body, there's this parallel, just like these sponges and water and material in this collage are porous and almost empathic. I like the way trees process and help us. I feel like the body in this image, you're like, you're in this state. And it just feels really intense to look at your body in that image. And then the leaf.

And it reminds me of a lot of the work that I learned about when I was making photographs with myself many years ago. And I was really influenced, actually, I wasn't influenced, but I was affected when I saw Francesca Woodman's work or Ana Mendieta and this relationship of the body to expressing emotive processes or this relationship between the physicality of space, architecture, land, earth, and the body. Like, I don't know, I feel like as women we perhaps have some direct connection to this energy of earth and expressiveness just with our bodies. Just the presence of your body to me is so symbolic, but also I can just feel what you're feeling somehow.

MB Yeah. I definitely don't have to say, it's very rare that I'm sharing these. They're not posted anywhere and they're not— I always start with photos of myself in the work because I just do, but I don't always talk about it. It's almost like it's so obvious that I don't even think about it. The fact that I literally am a processor. I'm a processor, I'm a processor of life, of death, of you know, just on a physical level. Women, we—

SR We absorb and we transmute.

MB Yeah. We carry life in, and in our bodies. I was also thinking a lot of times, like when I'm looking at imagery of outer space. For a brief time I became obsessed with them. They figured out that when the egg is fertilized, like when the sperm fertilizes the egg, there's this flash of light, this color and I just, that just to me is so interesting and no...

SR It's mind blowing actually. That's amazing.

MB And if you look at, so I want to get into talking about James Webb a little further in the next image. But there's all these things inside of our bodies that reflect outer space and the sky, which is just— we're like these ecosystems. So it's like I can't do the physical element processing, the ability to process combined into the artwork is just something that I don't think anyone can separate. And I just, I think that people either choose to talk about it or not, or maybe they don't think about it, but I don't, it's there because you're making objects.

SR Yeah, it's like the energy flows through us and we are expressing, we're like, we're so enamored too of nature and these beautiful objects you collect, we're like the witness of those things, and we're seeing them and feeling them, but then we have this feeling I do anyways of like a responsibility to then create with that knowledge and like express something else. Like, so, so when you're making a painting, you're like, where's this coming from? And it's almost like it's coming from the memory banks of everything you've experienced. And you can't really pinpoint it and say, oh, today I'm going to make an image like this. Sometimes you could, but the way that you're working is a little more fluid and abstract. And there's like these reference points and you're an absorber. You are the camera.

MB Yeah.

SR Right. Your own recorder and the way things come out of you are multifaceted. They might just be oozing out of your presence or they might be left in the tracing of your body on a piece of paper.

MB Yeah. So the next photo— I kind of brought in, I started to bring in these paintings. Because what happened is one day with the collage stuff I was just like, I'm done. I don't want to, I don't need to collage anymore stuff and so I started painting and what I was doing was I was, I was dipping the paintings I got, I'm really getting into this thing where I'm like using acrylic inks and some different combinations of things, but then I'm also using like marbling paints and I'm dipping them in this water. What started to happen was I just wanted to see that light or those shapes in the collages. I just wanted to bring that into the paintings.

And I have these big four by eight foot pieces of foam core. And I had turned all of the surfaces. I had the whole studio filled with like, perfectly organized collage things. And then there were collages on the walls. And then I started painting. And I was just hoping that through osmosis, that something would come out in the paintings from the collages. Like the collages were almost like a journey or like if sometimes if you fly, like sometimes if I have a dream and in the dream, I'm flying, I'll be flying over water or I'll be doing like, exploring something like that in a dream. So the collages were sort of like that. Like I felt like I was kind of flying or walking or moving through. So then the paintings are like a way more— those are really what comes of it all, the distillation of all of it.

SR They're very watery too. Yeah, they're very watery and like, I mean, they're all, they're birthy and they're cosmic. They're look like planets and cellular molecules or something. They look

MB Exactly.

SR And they also feel like, like the sand and the ocean, but they're so colorful. , they're otherworldly and yet very tactile. That's cool. Yeah. You said that you built them, so these are thick frames. Is this what you meant by that they feel like these objects?

They're boxes that you're painting on the front of.

MB So they're, they're square. They're like small square canvases that are–

SR They fit, fit in your hand, right?

MB Yeah. They fit in your hands. So what happened was, I was making these collages and I started doing some paintings. And then this amazing woman who has a gallery called Vorderzimmer in Brooklyn, asked me to do a show. As soon as she asked me to do the show, I was like, yeah, I'll do the show. And it's gonna be from one solstice to the other. It's gonna be from that day that I was sitting in Shake Shack on Newbury Street and realizing how hard the pandemic had been to this following December, where all these people are gonna come and gather together. And it's gonna be the darkest time of the year, which is always my favorite time of the year when it's dark and cold and snowy.

I think I should say one thing I want to point out, we just talked about, the very intuitive side of all of this, the side that can't be defined, and that is a mystery. But there's another side to it for me, which is a very organized scientific way of doing things. And I am very, very organized. I studied color theory in school. It's very important to me. The links I was sending you about the camera obscura. So there's a side of it that's very organized, and scientific.

SR Yeah. And you were a photographer too, so there's this other aspect to you. Yeah, that's like–

MB And that's very organized, that's a very clean sort of more— So I was looking at the James Webb telescope imagery and I was cutting out stuff from that. And then these were just like some paintings that happened. There were these weird wings that started these wings shapes that started appearing. And I was thinking about when we're looking at the James Webb imagery, you're not really looking at a black hole. You're, you're looking at a group of scientists who have assigned colors to the different rays of light and the different things to bring the, you are looking at like a combination of many images and of many scientists input. And then I started thinking, well, how do they pick, how do they decide the colors that they put into these pictures? So these pictures are beautiful, but they're really a combination of imaging and imagining. They're not just accurate, you know here's a black hole. That's not what it looks like.

SR That's really good to hear because I've been looking at them thinking like, "Wow." But I know they're "Wow," but there is artistry happening. There's human involvement in the way we perceive outer space.

MB Oh yes, totally. And then also just the, if you look up the James web, the camera itself, the spacecraft is beautiful.

SR Sculpture.

MB The whole combination. So then I started thinking, well, these neon colors—which, I love to paint with fluorescent colors.

SR Me too.

MB And I always was thinking, what is the history of those? I started reading about day glow colors because I was using a lot of fluorescents in these paintings. And they just really, to me it's like painting is light. Photo photography measures light and records light, but painting is light. Like paint pigment reflects light and you're painting with light. So I started thinking, well, who invented the first fluorescent color? Well, so there's a company called the DayGlo Color Corp, which is in Cleveland, Ohio, which is where I'm from. It was these two guys, their dad owned this paint business. They would mix stuff up in their mom's laundry room. They needed paint for their magic show. And they came up with paint that glows under.

The black light. They then figured out how to make the colors fluoresce in daylight. So that's why it's called DayGlo because you don't need the black light to make these colors glow. It was around the time of World War II, which is also such an interesting time in our history for so many reasons. But, so they started, they were using the paint so that planes could land without turning lights on. They were using it in all these interesting ways and they were putting it on orange cones. , so I just kind of did a deep dive into that.

Where do these fit on the color wheel that we've all been studying since the first color wheel was made. And they really are just enhanced light reflecting colors of colors that are already in the color wheel. So they're new. This is all in our time, our century here. These are so new to painting and art and to the world. So that is very interesting to me.

SR It's sort of like that moment when photography was new too.

MB Exactly.

SR It almost doesn't feel like it's a respectable piece of art if it has fluorescent in it or something. Like they sell it at the target for the kids, and I'm always buying the fluorescent colors.

MB Right? Yeah.

SR There's this sense of otherness to it because we haven't seen any reference of it.

MB I think about that a lot because I studied at a hardcore traditional art school and you had to make your own rabbit skin glue. And you had to know how to do oil painting. And so for me to be painting in these high pigments, acrylic paints or even acrylic washes. I work with private art collections in my day job, and I know that we all know that oil paintings sell for so much. I mean, maybe it's changing now, but there's certain types of things that just sell for so much more because it's an oil painting.

But we have all these new materials, right, that people are discovering every day. And it's important to learn how to work with those too, to be able to master those. So to me it's, I definitely think when you see a glowing orange, pink, yellow painting, it's like, oh, freaky. But it's also like, no it's what are we doing here? This is something to be mastered. It's something I started getting really into with these, these little paintings. And I think just the culmination of—sort of going full circle, of starting off with those pictures in the beginning. It's very stark. There's nothing there, there's a lot of space there for nothing.

And I think as an artist, you take a chance and you dive into nothing. There's no meaning. There's no reason nobody's telling you to do it.

SR Yeah.

MB And then this world unfolds. And so by the time I got to the paintings, these paintings were just like kind of making themselves, they were just the little paintings, they, it was like, okay, yeah, this makes perfect sense. These are small, you hold them in your hands. These are little pieces of outer space that you can hold in your hand and give to somebody. These are little expanding worlds.

SR Take them on the train out to Montauk to have the right beach experience with the Purple Sand.

MB Yeah. But then I guess I just want to end with saying I had an open studio in October and about, I don't know, like 200 people came through here.

It was crazy because it was the first open house in New York and the Navy yard participated and they really pumped it up. And so I had all the paintings up and I had all of the collages up. The thing that was really interesting to me was that people responded to the paintings. That's what they responded to, the collages, they kind of looked at and they were just, there's like the table of curiosities, all the different things that were collected. People wanted to see more of the paintings and they just loved the paintings. The collages they thought had been done by someone else, a different artist in the space. Like they thought I had a studio partner. It was just really interesting to see after being in isolation and making work in here alone for so long and then to have all these people flood through.

And it was just so interesting to me that they thought the collages were made by someone else. Then I had the show at the little space and almost all of the paintings went out into the world, almost all of them. And I think it's because they were small and accessible. But if I made them go out into the world specifically, which I don't always do, most of the stuff is for me, I don't even know if it matters if somebody sees it. But these, it was very satisfying to have them go and they went to all like amazing people and they're gonna be in their house. And I love it. I'm so glad. And I feel like there's like a little bit of me there, which is really fun.

I think that when you, like when you grow a plant, right, the plant has its preset thing that it does. And it, it, it's doing that and it takes a long time and it's building up cells and it's, it's growing. But I think it's the same for an artist, and I think it's each artist. I mean, I have this deer skull sitting here that I've been looking at that my dog found, and there's all these layers in it, and you just see how this deer grew into what it was supposed to be. Right. And I do, I do feel like artists are like that. I feel like maybe not all, but I, I feel like for me, I can't necessarily see it and I don't need to see it, but I need to keep growing it because the growing and the layers and all, anyway that I approach it, at some point you're gonna be able to look at that and know that I was there. It's funny because I don't think it's totally happening yet. It was so interesting to have these people be like, who made these? And I thought, well, God, they, they look that different. But I don't think it's like an easy overnight, it's like a lifetime that we spend growing our, whatever our practice–our specific thing, you know?

SR Yeah. And also what you're making now is reflective of what you're thinking about now and what you made for this show in December was reflective of the previous year or two experiences. So I'm totally okay with disjunctive or transformational practice like that you go from one thing to another makes perfect sense to me. And I love looking for the thread, but sometimes we don't find it and it's okay, we're multifaceted.

MB Right, right. But it's–

SR Like, I know, I know that part of you that is the photographer and that is very exacting or, but in the end, it, it's not the material that matters so much as your process and your, your interest, your you're digging for something and you're exfoliating, and there there's like this, there's this conversation that's developing over time. And then sometimes they're in the individual piece. Sometimes they're between the pieces. And then I love this idea of that it's just this presence of like, you might be gone, but you'll know that you were there.

MB Yeah. Yeah. And I think I think for me I don't always want to know what I'm looking at. And I think that this, this body of work, and I think the pandemic one thing that really struck me during the pandemic and then the beginning of the war in Ukraine was when people say affirmations and they say, "I will be taken care of today and everything," we have all these affirmations and things that we do tools to help ourselves. But I, there was a point where I was like, actually, I think there does come a point in life where you have to realize. You really don't know. We really don't know. And I think that it is important sometimes to acknowledge that, even though it's probably not what someone wants to hear if they're struggling with depression. But I do think it's important. And I think that one way it can be acknowledged is through art. I feel like it's better for me to acknowledge it that way than to just alone weather it and be isolated.

SR Also as I look at your painting, and I know that you might have been in that we really don't know aloneness, despondent space, it's still a transformative act. And when I look at it, I still feel I'm given so much hope and so much opportunity for growth. Like, I don't know what the image is about per se, but I feel like connection and expansion, to me, that's, that's more compelling than just staying in one's own head and not doing anything. Like you, you actively worked with it, you're conversing with the experience.

MB And it's also just, I think it's, I think one of the biggest and most major affirmations for me anyway, is just that there's always gonna be an unexpected, beautiful thing. Always, even if it's just one little weird brush stroke on something that just all of a sudden is so beautiful. Or just looking around and being like, oh, there's, this is per, I'm standing in the middle of Purple Sand. There's always gonna be unexpected beauty. And I think that that is, we're really lucky that that can be there. Yeah. And then we can try to be able to see it, you know?

SR Yeah. I'm just still kind of mesmerized by your photos and your words, and I've really enjoyed spending this time with you. I don't really think there's an end to our conversation. Should we pause?

MB Right, exactly. We'll take a pause.

SR It's great to talk to you, Millie. You're fabulous. And I love the not knowing that we've spent together. Thank you.