Inside Art Episode 2: Rodrigo Valenzuela

Published:

April 13, 2023

Artist Rodrigo Valenzuela makes dramatic photographs of staged scenes that question notions of work, capitalism and the unspoken history of landscapes.

Los Angeles based artist Rodrigo Valenzuela constructs staged scenes with machine parts and metal fragments to create dramatic photographs that reference architecture and art history while questioning our relationship to work and workers. His diverse practice also includes printmaking, sculpture, installation and video. We talk about capitalism and the idea of a post-worker world, subjectivity and memory in relation to landscape, and his labor union roots in Chile.

As head of the UCLA photography program Valenzuela finds that expressing his ideas as a professor often makes a bigger impact than being in shows and exhibitions. He talks about his commitment to teaching, giving confidence to students to express themselves, and enabling self-discovery.

Listen on Apple, Spotify, Amazon Music, Google Podcasts or wherever you listen to your podcasts. Or watch on YouTube.

“Photography has this very interesting friction with reality… I think because photography has this relationship with the real. Often we associate the real with immediacy.”

Video Highlight

18 min excerpt from Episode 2 with artist Rodrigo Valenzuela.

In the artist’s own words:

“I construct narratives, scenes, and stories which point to the tensions found between the individual and communities. Gestures of alienation and displacement are both the aesthetic and subject of much of my work. Often using landscapes and tableaus with day laborers or myself, I explore the way an image is inhabited, and the way that spaces, objects and people are translated into images.”

– Rodrigo Valenzuela

Rodrigo’s links

Website: rodrigovalenzuela.com

Instagram: rodrigovalenzuela_studio

Images mentioned

New Works for a Post Worker World

Recent show in Florida: Layered Land at Mindy Soloman Gallery

Goalkeeper

American Type

Trilogy of Modernism

Journeyman

Artists mentioned

James Welling

Franz Klein

Aaron Siskind

Lewis Baltz

Fred Wilson (His exhibit Mining the Museum 1992)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s film “Zabriskie Point”

Writers mentioned

Harold Rosenberg

Clement Greenberg (His essay “American-Type”)

Galleries & Institutions

LA Historical Park project

Print Center, Philadelphia

BRIC, Brooklyn

Photo Art Fair AIPAD

Guggenheim Fellowship Award

Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship

Patricia Ready Gallery, Santiago

Mindy Solomon Gallery, Florida

Orange County Museum, California

Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Oregon

UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Photography Department

Bard College, New York

SVA (School of Visual Arts), New York

UPenn (University of Pennsylvania)

Documenta

Whitney Museum of American Art

Please rate and review this podcast on Apple Podcasts

Thank you for your support, it helps share the podcast with a larger audience.

Transcript: Inside Art Podcast, Episode 2 with Rodrigo Valenzuela

Sarah Rossiter I want to welcome you Rodrigo Valenzuela to the Inside Art Podcast. I'm super excited to talk to you about your work. Tell me, where are you, what are you up to? You're headed to New York?

Rodrigo Valenzuela Yeah, I'm going to New York. I'm in Tennessee right now visiting friends and in a couple of days I will go to New York. It's my spring break, so I'm trying to do something that isn't "work" for a couple of days, like some light computer work and replying to emails. I have this proposal for the LA Historical Park project that I'm doing in the spring. So I'm just taking this downtime to make sketches and stuff like that. Then I will be in New York taking a show down and bringing it to Philadelphia to The Print Center. That show opens April 14th and then I will do the Photo Art Fair, AIPAD on the 29th.

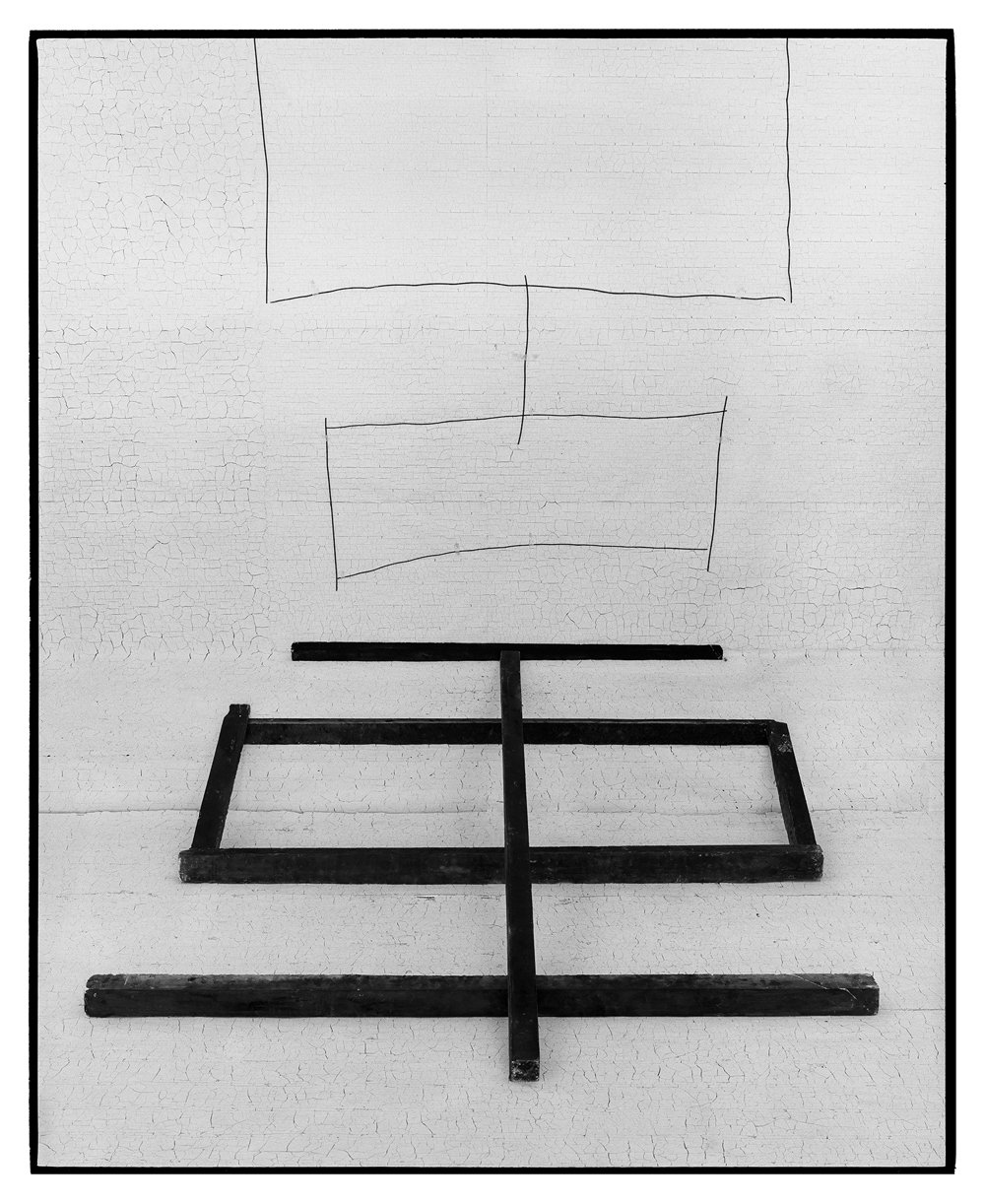

The work is already made, so I just have to move it around and then deliver the other body of work. And yeah, try to talk about a project called New Work for a Post-Worker World, that has been shown basically the whole pandemic and it wasn't a pandemic body of work – it was something that I was concerned with before the pandemic, but the pandemic proved me right in some ways.

So I did that show at BRIC (in Brooklyn) last September and then at Patricia Ready in Chile and now at The Print Center and then to the Contemporary Museum in Maine, in Rockland. Then I want to bring the show back to LA, but I don't even have my art in my home. So I think I would like to have it at least for a couple of months, some work in my house in case somebody visits, and they can believe me when I say that I'm an artist.

SR So you make photography, sculpture, installation, maybe video, and performative work. But how would you categorize the work you're talking about now?

RV Screenprints.

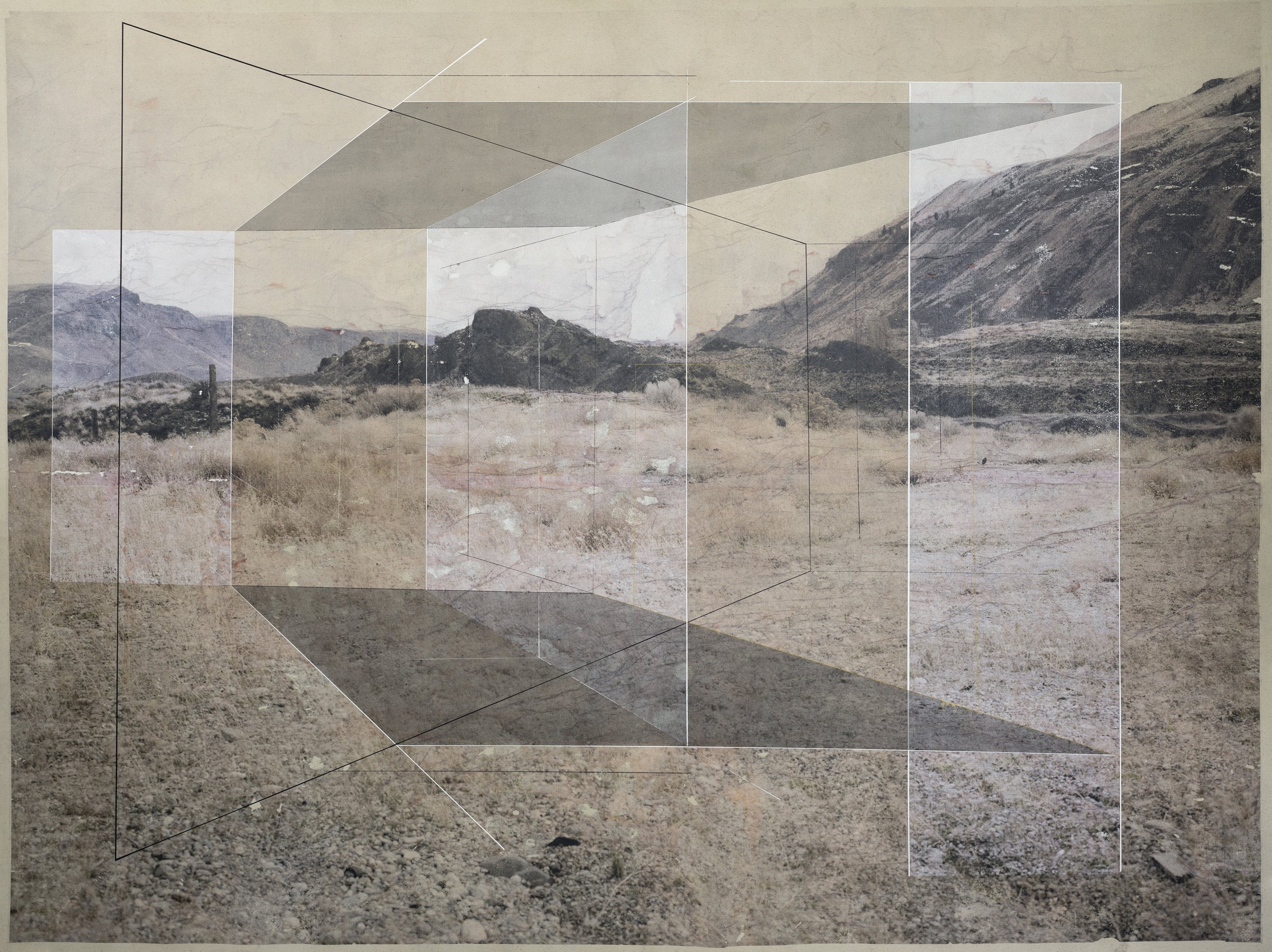

SR Screenprints, but they could be called paintings. They could be called photographic imagery. But also, they have this quality of drawing to them. They're sort of like geometric shapes that you've drawn on top of landscape imagery that you took.

RV My process has a mix of all these things at the same time. It's funny when you mentioned video work because I started as a video artist making very traditional-style filmmaking. My work is still kind of like documentary style, single channel videos. A lot of installations, but every show, I still show one video work, but I haven't made one in a couple of years because the ideas are just so ambitious that it is hard to think right now of taking two or three months off to make a video and spending around $10,000–$20,000. So a lot of time, the photos become a lot more recurrent. I'm not an expert, even if I am the head of photography in the best university in the country, but I lack confidence sometimes about the photographic quality of my work, so I subsidize it with a "salad" of other mediums that come to play.

SR I think your photography is really interesting, but it is different from what's happening around you. It's very unique. I saw your work for the first time at an art fair in LA maybe 10 years ago. As you mentioned, you're the head of the photography department at UCLA. So you're teaching and you're surrounded by a variety of other photographic and sculptural professors, artists. It's a really different environment. I think your work is unique, so I can imagine you might sometimes wonder, "Where do I fit in?" But being different is a great asset.

RV When I start shooting, I make objects. A lot of the time I'm in my studio trying to figure out what is interesting to take pictures of. So I'm never able to walk around with the camera or sometimes, when I go to a landscape place, I take pictures with landscapes and those sometimes become part of these paintings I've made. But in general, when I have a photo show or a photo project, I start by reading a lot, making folders and folders of archives and images and resources and watching all the movies talking about a lot of ideas to my friends. Again, between reading and making work, it becomes a very nice symbiotic relationship between new forms and ideas and the inquisitive nature of wanting to know more. This gets resolved by making more, and then, that creates more hunger for knowledge in some way.

So I have a pretty healthy practice in the way that I always wanted to make more because I feel a lot of the thoughts that I've finished that there is more, even if that kind of discourse or that idea in a particular show is capped, because I just max out my creativity or my output or run out of time, and then I move on. I don't have any kind of resentment about not being able to say everything. I don't know everything I will say or have certainty about what it means. A lot of the time, I leave it very open on purpose.

SR Yeah. Your work does feel like that you have this really interesting practice of physical experimentation in the studio and then this other intellectual thing that you're doing when you're starting to prepare these photographs or just conceptualizing your installations— you're working on many different levels. I just wonder, has it always been that way or did it develop over time through doing shows?

RV Both. I think it's hard to teach in a school because it's something that you have to be good at. It's not multitasking, but there is a lot of parallel thinking. You can think with the books and you can think with the making and you can be making when you don't have any thoughts, but I also really doubt that you're not thinking. Sometimes you're not thinking very grandiose or complex thoughts, but say you're thinking about your food and if you really question the cause of your eating habits, there is a whole cultural paradigm there, right? It's a whole reflection of society there. The way you feel, who you want to hang out with, the people who you forgot to call— all those things that are not relevant, if you really make an inventory of those things, they are a very big window into who you are and what your concerns are.

A lot of the time, I think it's society-driven too, where I just make stuff and I don't know what it is, but I know that I have to go to work because I really think about this idea of making art, of being an artist, thinking something and making something is part of the job.

SR What is the title of this series that you've been working on?

RV It is New work for a Post-Worker's World. Then I made Weapons, and then I made Afterwork. The series started with Afterwork and that was the thing that led to the body of work, which was unusual... I got the Guggenheim Fellowship Award in 2021 which allowed me to really spend some time making art at home. I also got some fellowships from the university, and I also got the Smithsonian Artist Research Grant. So I had access to a lot of archives from the government, and I had some extra cash, and I had a lot of time in my studios at home. So it was kind of magical for an artist to have all this time, and all the shows were going to be canceled.

The thing about the subject matter that I had proposed for the Guggenheim, and that I proposed for all these fellowships was about the decline of labor unions in the USA and the necessity of having them or the spirit of them, right? The fact that people don't even miss them is the problem.

SR Just to give some background, you grew up as the son of an organizer?

RV Yeah, my dad was a pretty leftist guy in Chile. He was part of the sindicato de cartero in Chile, the mailman's union. And I grew up during a dictatorship, and then with the transition to a democracy with a socialist president—all the benefits I have, I grew up so poor, so a lot of the benefits that we had, including the apartment I grew up in and the vacation house where my parents would take us, they were all part of collective bargaining rights and collectivity. So the power of collectivity really helped us to have a better education and at least a place to go for vacation. I went to the same place for 20 years growing up, but it was a very nice place where you would run into the same people and there were other mailmen hanging out with their kids for vacation. The same in the house I grew up in, they were all state workers, so everybody kind of has the same class and level of education. It was very interesting growing up in a socially unified place, beyond money. A lot of ideas come from that about space and belonging and things like that.

The ideas of the work started when I noticed a decline of collective bargaining rights and unionization. When the pandemic hit, I wasn't worried about the home or staying home. I knew immediately it was going to be an opportunity that people would have to dissolve any sort of brotherhood or sisterhood or fraternity between workers. I think the pandemic created the perfect conditions for employers to take away rights.

So I truly was like, "This is the thing that will accelerate that." I mean, the Post-Worker's World title is specifically because I don't think people will be jobless. Part of the fallacy that people make about the future and technology, automatization or the internet or computers is thinking that it's going to steal their job and that is the boogeyman that people use. The thing is, as long as there are rich people, they are going to need to exploit something. That is it, rich people exploit people. Capitalism is designed for people to be exploited, right? It is gonna be people in third-world countries like clicking, doing the automatization—flagging images, reviewing products, dropping information for AI, whatever it is, there is packaging stuff, shipping stuff, working in warehouses. Whatever it is, there's somebody who is always going to be exploited. But the idea of being a worker is the thing that's going to disappear.

Among the people that are in the USA or in countries where people can afford to stay working from home. When you have that as the spirit it becomes very dangerous because this is what capitalism wants. It's like divide and conquer, really. The empathy that is required to live in society will be gone because you never take the bus, or take the subway. You are never encountering the person that cleaned the office. You are never talking to your boss, there is a lot less social mobility and socializing. So all these "bubbles" that get people like Trump elected and make you believe that you and all your friends are right. So you obviously don't even need to vote because everybody you know is voting for the same person you are, so why even bother, right?

So I think those bubbles are gonna be much stronger and because of this kind of disappearance of the worker. So I think a lot of technology and fear doesn't have anything to do with not having a job, but the post-worker war is real.

SR So should we look at your images of what you're talking about?

RV Yeah.

SR Let's see what I got.

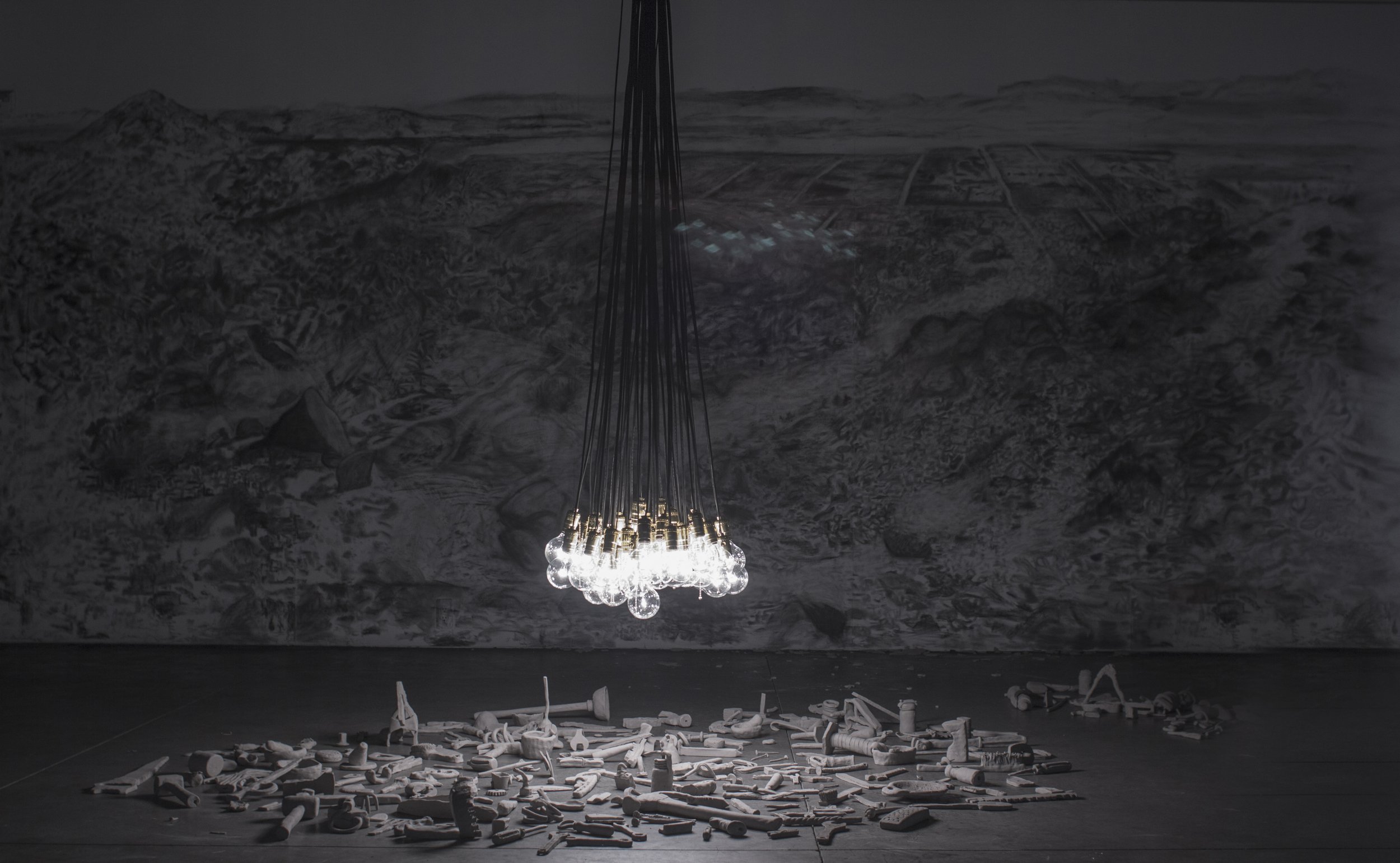

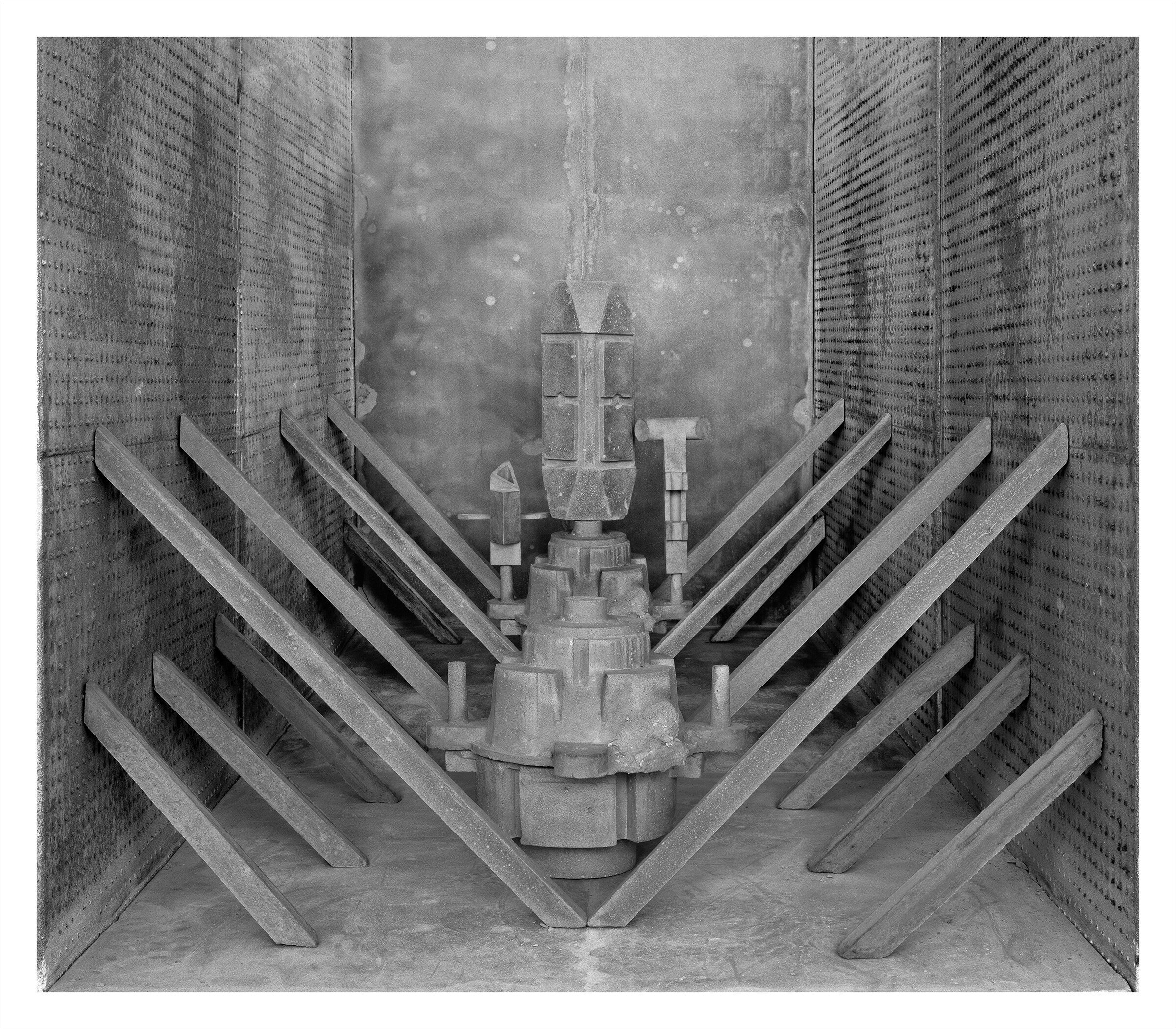

RV Oh, yeah. That is an exhibition at Patricia Ready Gallery.

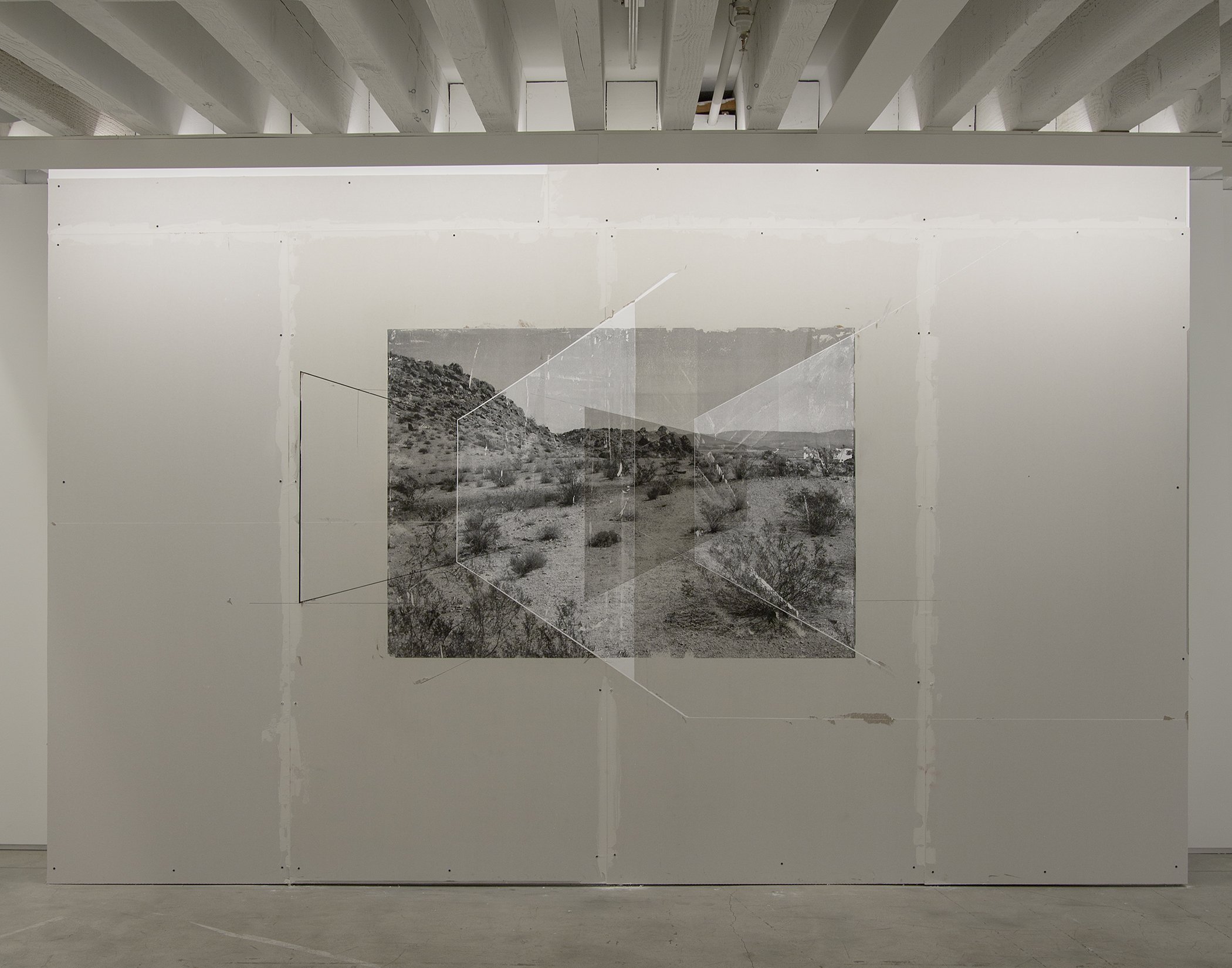

SR So I've got that image, which is the installation, and this is called New Works for a Post-Worker's World. But then also on your Instagram, I was looking at this image, so this is from your February show in LA, right?

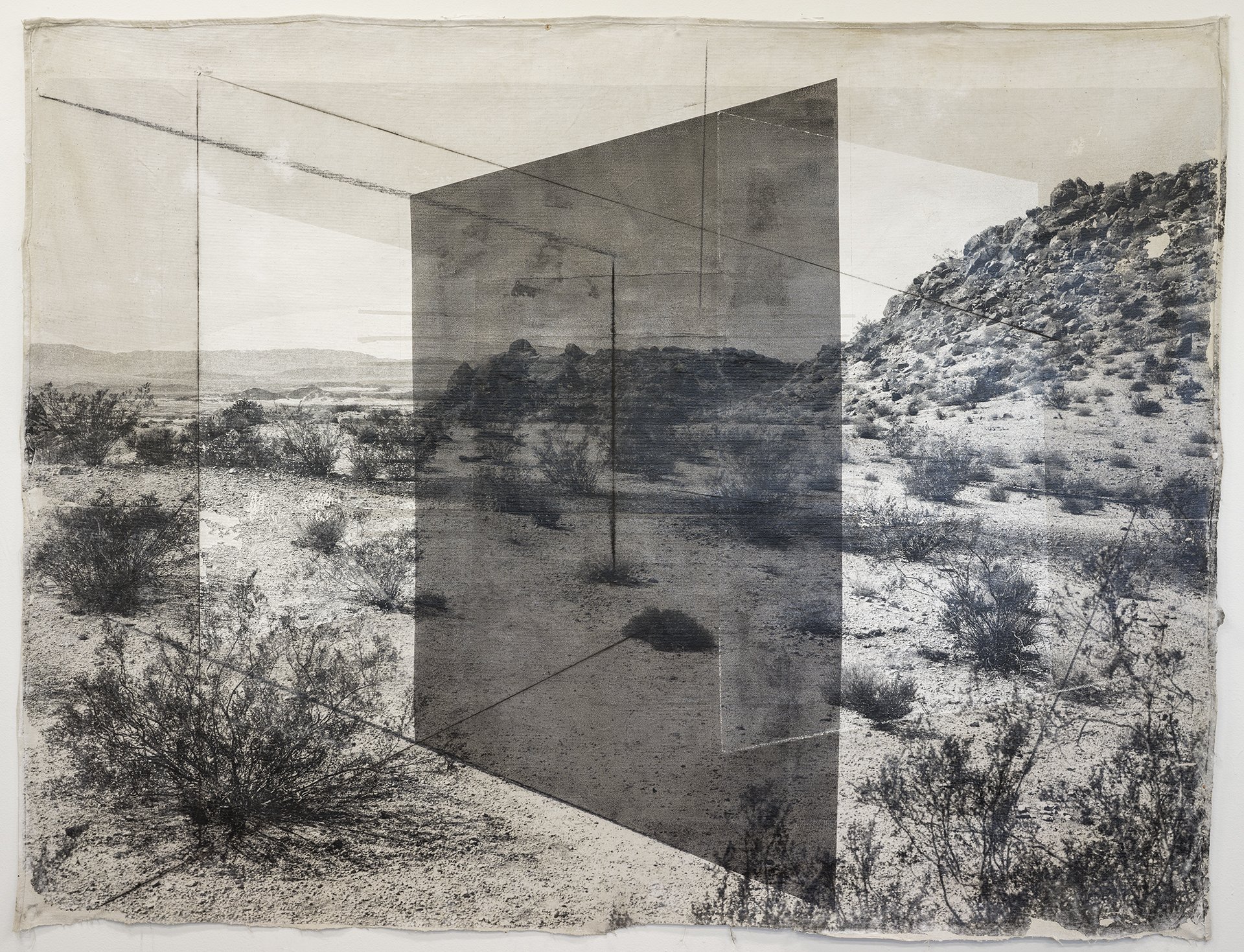

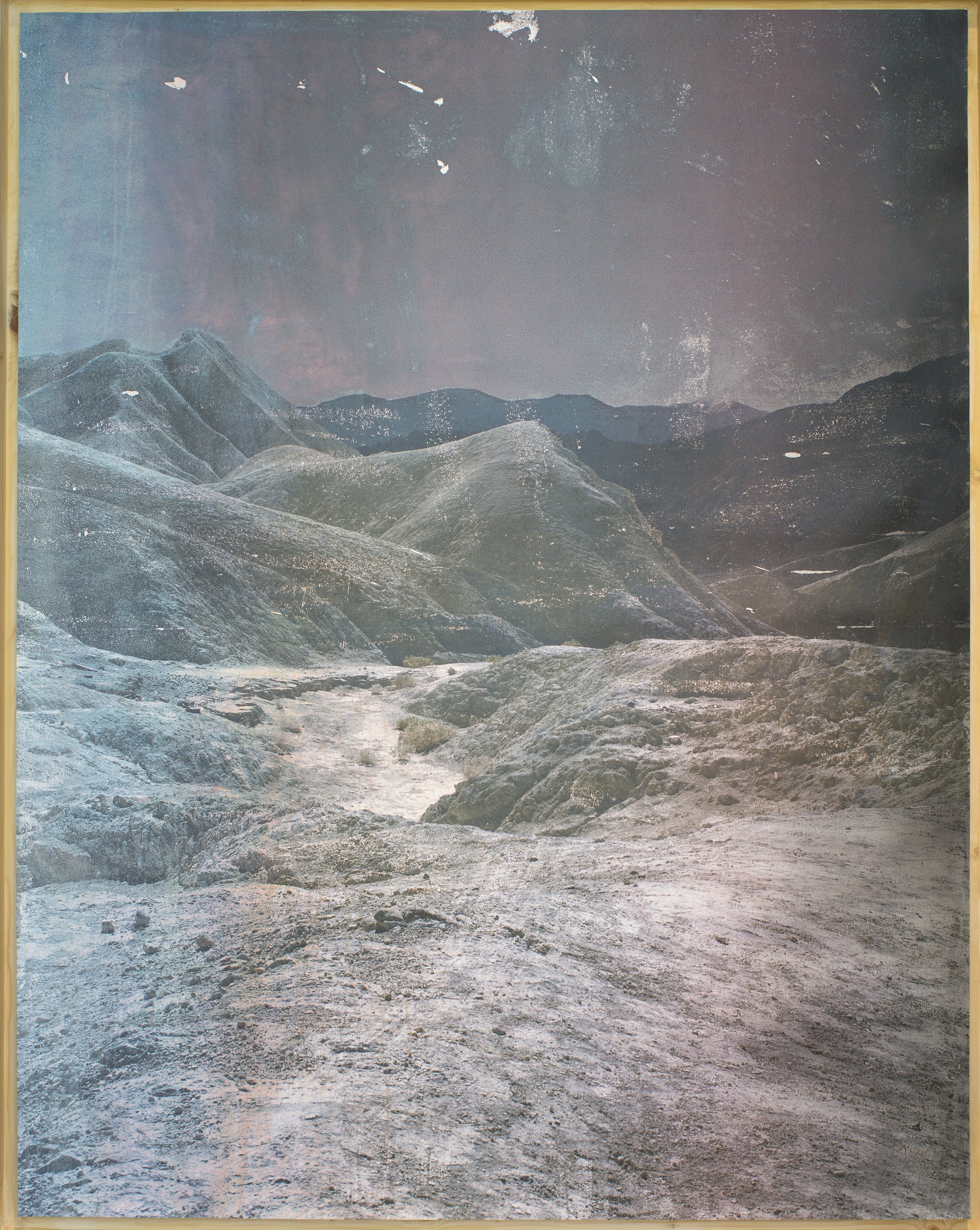

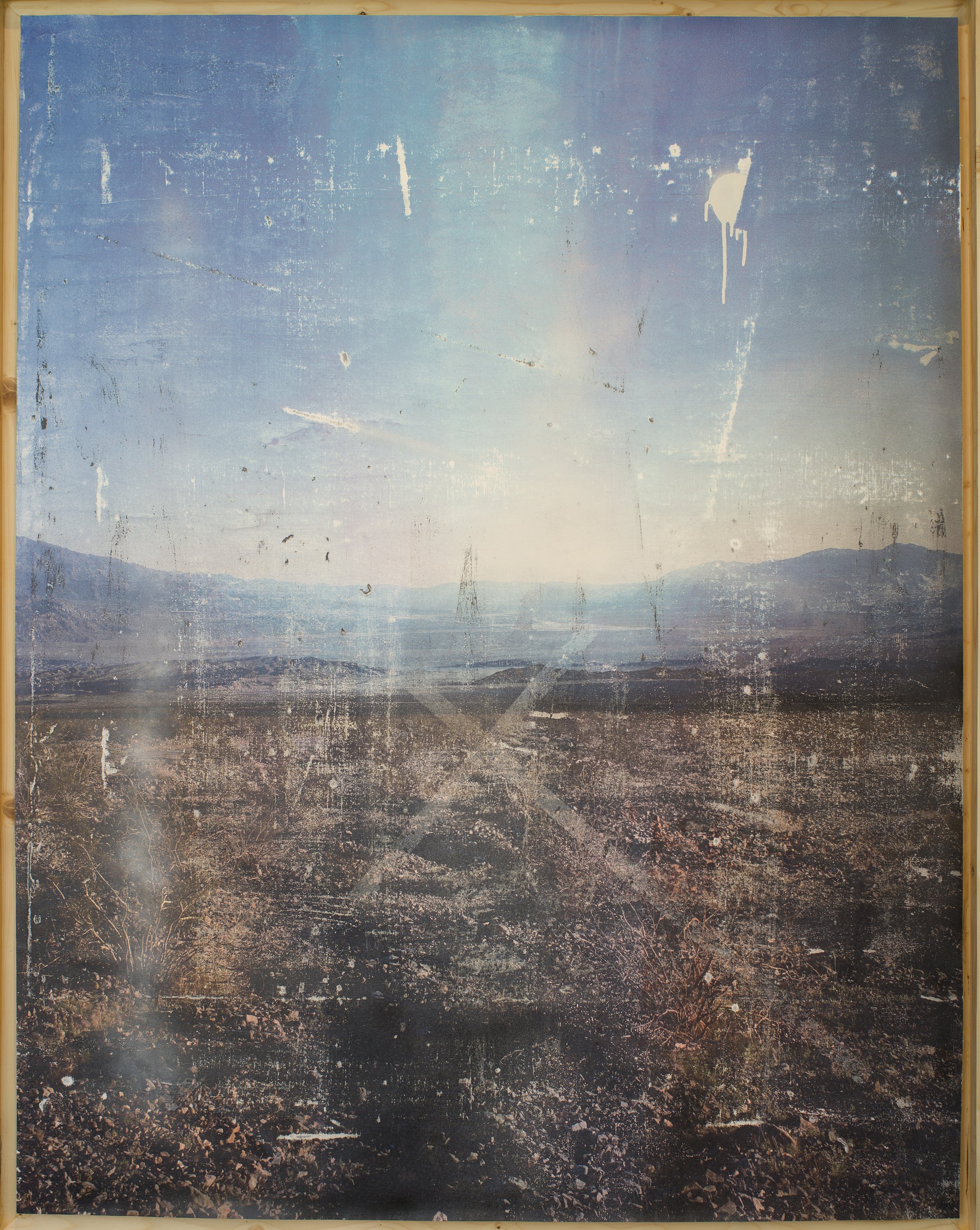

RV That is for the show I just did at the Mindy Solomon Gallery in Florida. I've been making these landscape photos from the Atacama Desert, and I do it here and there. Sometimes the research gets a little heavy, so I like making these landscapes. They're quite beautiful and simple but they are super dark in some way, right?

Because a lot of these images come from a place called the Atacama desert, where thousands of communists disappeared during the dictatorship. So the original idea, when I started making these landscapes seven years ago, or maybe six years ago, I was thinking about building a city in the place where all these people disappeared, where socialism and communism disappeared. There are so many ghost towns there because of the exploitation of natural resources.

For example, to make a weird connection, if you look at my website again, the installation of those images that you have here— the idea when I started the project was to make something that would look like bunk beds, like a very abstract installation of bunk beds.

SR Bunk beds, okay.

RV In the 1800s there was this thing called "camitas calientes," like hot beds. That was when workers had two shifts or there were three shifts of work and people would come back, take a shower, and then wake up their coworker. The coworker could go to work, and then the guy could go to sleep in the same bed. So the beds were always hot, but there were always warm beds. So I was trying to make an abstraction about this.

One time I did this project in North Dakota about the oil industry, and they have all those "man camps" there and they're very interesting. They're lonely, even though they're so full of people, they're super lonely, but also it has to do with this like hyper-capitalism—they don't let people live or sleep or be happy and have a normal life.

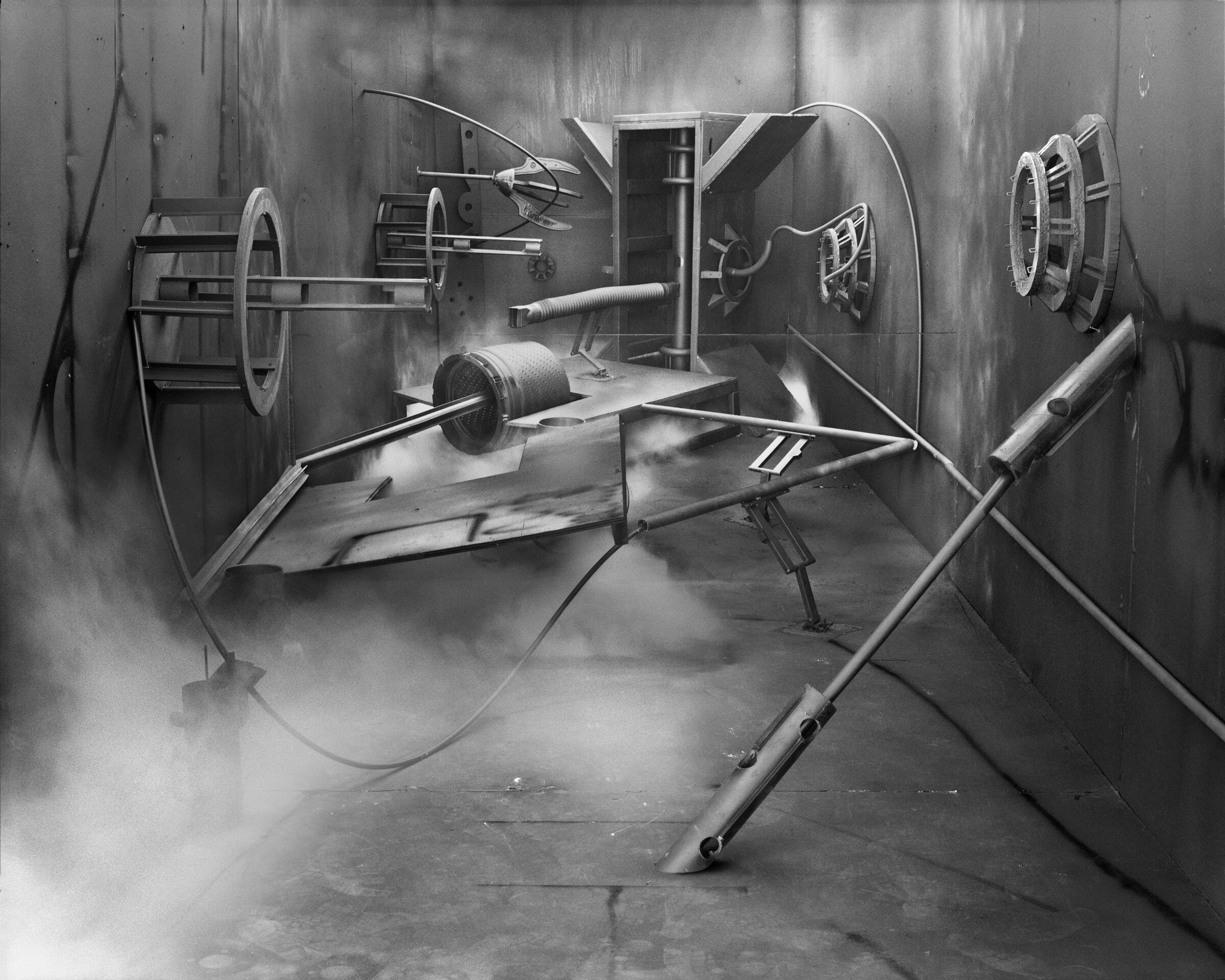

You have to devote your whole body to the production of goods. So a lot of these images have that "ghostiness" of the machines and the spaces and the steam can be the sweat of a person or can be their ghost—it can be their soul that is no longer there or it stays there after they're dead. So there's a lot of possibilities and readings for the work.

SR Yeah. It's intense. So you make this installation in your studio—in case anyone's listening in and they can't see the images, I'll share this video with the podcast link later—but you've got all these incredibly heavy metal machinery parts and you create a collage basically, in the space of your three-dimensional studio.

RV Yeah. There is something about when I make the work, I look into the viewfinder a lot and there are images that I want to see.

Because I didn't go to art school. I don't know if I mentioned it before, when I met you, I never had the thing that you had, right? You had like eight other people to make art with, and then you all had the same kind of mindset and made art with your friends as a social activity. Yet at the same time very seriously considered. I didn't have that and I usually have to look through the viewfinder a lot. To really think about...

I am the only audience for the work sometimes, for months. So I really try to make my work very interesting or very complicated because I don't have all those voices to run through ideas. I have to do all those things by myself. I really want my images to be interesting for everyone. Even if somebody may not have formal training, I don't want it to be like, "You can understand this work if you read about this guy and watch this movie. And you also should have been there when I was thinking this thing to totally make sense." Instead, I really want them to have something.

SR I often feel that artists' imagery is sort of like a portrait of their mind and how they think and how it helps me to understand you by looking at your images. So as I listen to you talk, I am hearing all these other layers too, but just in the image itself, it's incredibly complex. It sounds like you're talking about isolation and creating your own world where you can make sense of and explain to others what you believe—how you see the world, what things are working, and what things are not working.

RV It's not so much isolation but I really think about the work as essays that I make. And I really like the idea that I may be wrong. I do a lot of research to not be completely wrong, to not be ill-informed or not to be ignorant about some things, but also I think having weird theories and thinking out loud, the work being the thing that you use to think out loud, is very important.

I think the art world is not cool enough or interesting enough to not be able to give your opinion or to fantasize about a better world or to do something that you think is necessary. Making paintings or making photos like somebody else does it to try to become part of a trend. I mean no one in their right mind wants to be part of the trend, but to almost respond to something immediately, to really be part of the conversation, but I just think if people aren't proposing new conversation, then the conversation sucks. To me, just doing proper research and then whatever feels like preparation to satisfy certain needs and give me confidence in the creation is enough.

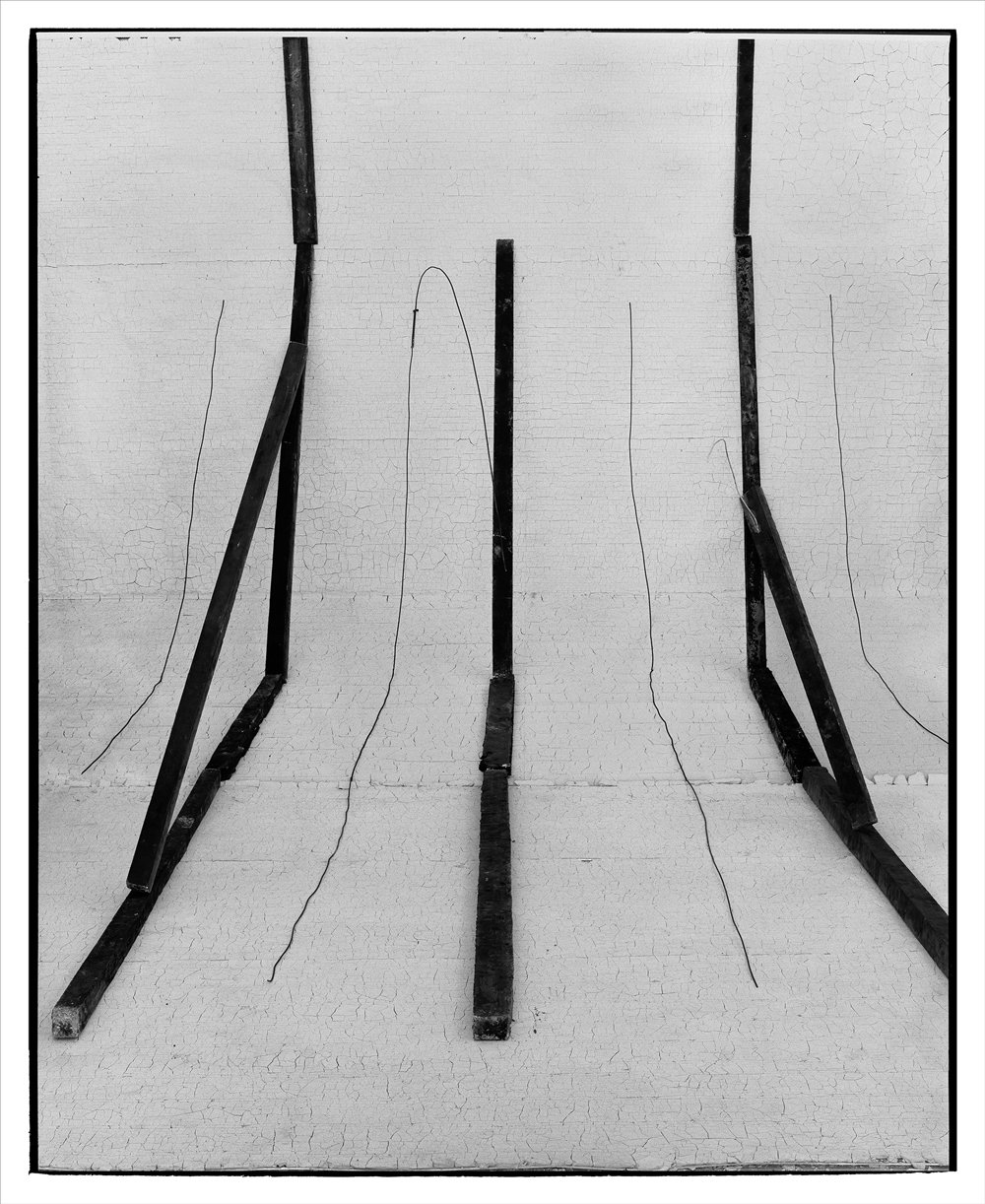

SR Yeah. I'm looking at American Type on the screen, and I just wonder if there's anything you can share about this experience, because on some level it's really hard for me to superimpose all of your thoughts onto this, but I'm also really curious—what were you thinking when you were making it?

RV That is the first body of work from a trilogy that I've been making about Modernism. I think the period of time and also the political repercussions that Modernism had in the rest of the war, and mostly from the American perspective, is very impressive. So basically with the work, I was thinking about all those conspiracy theories – that the CIA sponsored all the American abstract expressionists, especially the writers like Harold Rosenberg or Clement Greenberg to elevate the American arts post-World War II to a level it's never been to before. The ideas that they had were profound and interesting and playful and obviously, now in the 2023 reading, you can be like, "They're a bunch of white dudes," but independent of that time, the ideas, I thought, were very radical and a lot of the political content of the world was in the lack of iconography and the lack... And the gesture, the power of the gesture was super present. The gesture as a carrier of the political content, as a representative of the intentions of what you want the whole art to embody with every fucking painting, I think was very brilliant. It was brilliant and sad and weird. I'm not a huge fan of any of those guys, but the thing is, for me, that was enough to try to make a project about it. There are a lot of artists that have touched on it. I have seen, before me, the person who had my job before, James Welling did a project about Franz Klein and Aaron Siskin did some projects about Franz Klein. But in my case, I really, really wanted to go to the studio and work as a painter.

Basically it was a perfect excuse to not think a lot because with a photo, unfortunately, you get asked, "What is this photo about?" I just want to make some... Because I had this foundation about Expressionism and American-type painting, and after the essay of Clement Greenberg I named this series American Type.

It was fun to go the whole summer and just try to make the most interesting images I can make and look through the viewfinder to find stuff I love. At the same time, I had a solo show at the Orange County Museum, where I was able to create a show with a lot of Lewis Baltz works. So I had this connection with Lewis Baltz and Expressionism that is very present when you look at the images. I curated this show with a permanent collection at the Orange County Museum, and then I was able to have my solo show.

So the two shows dialogue together, which was kind of like a cheating system to incorporate my work into a cannon. I made all the permanent collections of photography look like I'm the next part. But also, it's like I had the freedom to put myself into conversation. I had a solo show and with the other works I picked a lot of artists I admire and love, and I was able to play with the consciousness of the museum in some way.

SR Sounds like there's a lot behind the work. That's a lot of input. And yet, you're just in the body making the work in the studio, just feeling it. Not necessarily talking.

RV That's why there's some point where I have learned to do a lot because I teach. I have an all-winter (semester) where I'm teaching a lot. There's admissions, there is a lot of administrative work – when I do a lot of readings and I teach some classes that I want to research more. And then in the spring I read a little bit more, watch some movies, I start buying materials, and then in the summer I just don't research anymore. I just make work.

It's really helped me, this system, because it gives me confidence and also gives me motivation. By the time June hits, I'm super anxious to make work because I start buying some stuff, building some stuff, but I don't really like to shoot a lot in the winter. Mostly because my studio is outdoors, so I have it on my back patio. So all these images look like studio photography, but they're actually outdoor studio photography.

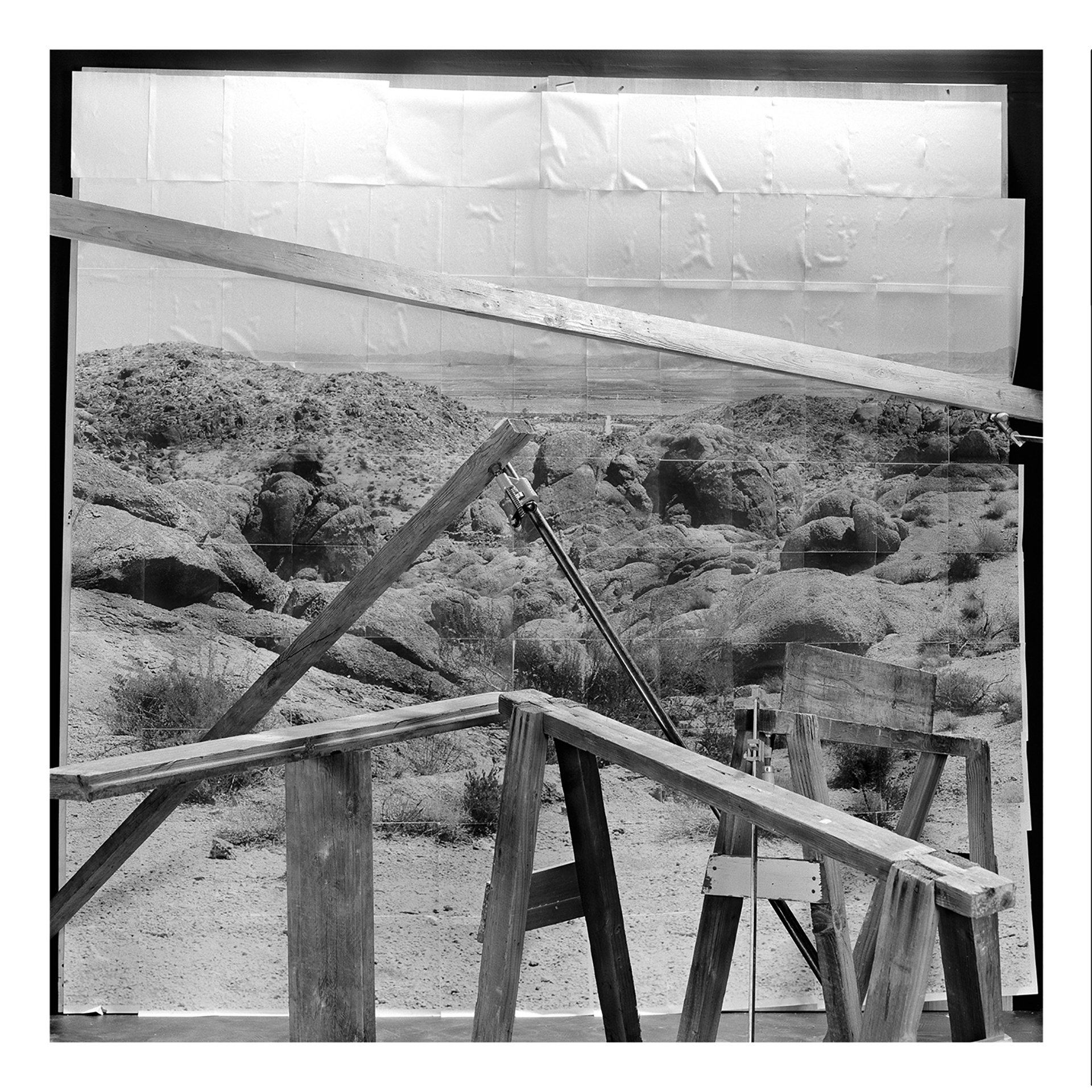

It's usually because of the materials that I get around to thinking about all this. For example, that image that you have now, the Goalkeepers, that's one of my first solo shows I made. It's a lot of the elements, the tools and the setup, the clamps, and stuff like that. But also to me, something that was interesting to think a lot about is how to use photocopies properly. I mean, it's something I've been using since 2014.

SR So the imagery is actually made of small sheets from a photocopier.

RV Yeah. Those are in the background and then I re-photograph that. To me, it's as simple as the American landscape. You have a lot of weight from Western movies to show the idea of manifest destiny. So when you think about America, you think a lot about this western expansion or New York or LA or whatever it is. But a lot of time you decide... Because I travel a lot, you meet Latinos or immigrants in Detroit and Omaha and Seattle or wherever you are. So it's interesting because when you think about America, what you're really thinking is, "What is the America people are thinking about when they are talking about it?"

SR It's very relative.

RV But truly that landscape doesn't really exist, the idea of America shifts so much from mind to mind, from eyes to eyes, that the only thing that is in common is the idea of a land of possibilities. But the land of possibilities is made by photocopies, which to me is the material of bureaucracy. So the only way you can become present in the country is to do a lot of paperwork.

For me, making this landscape sheet by sheet slowly with a lot of labor and with a lot of patience is how I became a resident. Eventually, I got my green card, and I was able to live and work here. There are always these levels where I have to have a relationship with certain materials to make photographs because it's the only way I can just keep working on it and do it and think a lot about them.

You know that image that you opened with, is super simple. It's an image transfer of Zabriskie Point. The project I did for that has so many layers that the images needed to be simple. As I've said, the transfer of the photocopies as material bureaucracy, the placement, the Zabriskie Point is interesting as the Death Valley, right? Just the name is strong, but also about the movie by Michelangelo Antonioni called Zabriskie Point. There are a bunch of young people trying to form some sort of labor union, and they get killed. They felt miserable. The movie sucks too. So even a movie about labor unions with an amazing filmmaker will suck, you know?

So those landscapes went into... If you goto installations and then you click on Work In Its Place. I used those landscapes in this box I built in the Jordan Schnitzer Museum in Eugene, Oregon. So the landscapes were outside and inside if you go forward in the images you'll see... So, the box is made with past walls from the exhibition. You can see through the cracks of my work, images from the permanent collection of the museum. So you cannot enter the permanent collection, you can only see it through the walls.

I was really thinking about protagonism. I thought it was a great idea because every city, every little town, has a museum with a terrible permanent collection of American art. So I was like, "Well if they let me dialogue with that, I can have a show everywhere. This show can travel and it is gonna be the cheapest show they can have because I can rework all the walls, recycle all the wood that they have in the back, make these stages cheap, those seven paintings are everywhere, and then just give them their terrible permanent collection."

But it looks like people don't want to, they take their permanent collection super seriously. So they don't want to be in that position. But the truth is, for a Latino or a person of color, to enter a permanent collection, you have to be exceptional. Then you go into the vaults of these museums and they have so much fucking crap—what is the merit of being in any of these fucking places? You have to get an MFA, get scholarships, go everywhere, and have shows all around the world so they can have a meeting and they take six months to pay you and they ask for a 20–40% discount. Then your work gets acquired and then it goes to the vaults and all that it takes for a lot of these people is some rich old lady donating all their permanent collection, and then everything gets there and you're just next to those pieces, you know? It's so ridiculous. I mean I'm happy with the installation. It still could travel more, though.

SR Yeah, it's a great installation. It reminds me a bit of Fred Wilson. I used to study with him in New York, and he would "intervene" in the museum installations in the Northeast. And I wonder, so this wasn't well received, you didn't get to do this again?

RV No, but people liked it. I really liked the installation and the idea, and I think when I give talks, people really like to hear about the project, but no one has ever shown interest in showing it anyway. But I'm happy.

SR Well, it's also like the audience, you know, perhaps those types of museums don't understand your work and they're really interested in the pictorial and the historical, sort of party line and your whole project is to disrupt that.

RV Yeah. I think you are very generous with their case.

SR Well, I don't know the specifics, but you know, some people don't like the boat to be rocked, but it seems like everything you're doing is questioning, in really profound ways and really creative ways. And you're constantly thinking and wondering, "What does this mean? How did this get to be?" And a lot of people don't like to realize their implication in the power structure.

RV Yeah. You know, it's funny, I love that expression, "rocking the boat."

SR I was wondering where that phrase came from, actually, because why wouldn't that be good? Like, don't rock the boat, oh because you don't want to fall out?

RV But I feel like it's one of those expressions where the emphasis of the words matter...

SR Which boat?

RV But it's also the ultimate kind of narcissist expression in some way because they don't want the boat to be rocked, but they're not addressing that you put it in the fucking water in the beginning, you know? If you don't put the boat in the water, there is nothing to be rocked. So if you don't want this thing to be rocked, don't put it in the water. Let's recognize that my body has some weight and that you invited me in maybe. Once you have an institution in a public space, the water, the boat will get rocked. Whether you want it or not.

SR That is the nature of interaction.

RV That's the nature of being in the public and interacting and being a thing. I think the only people that will be concerned with the boat being rocked are the people that see their job security depending on that lack of rockiness or lack of motion, right? So I love thinking a lot about American expressionists because it makes you really think a lot about where the energy of certain activities take place.

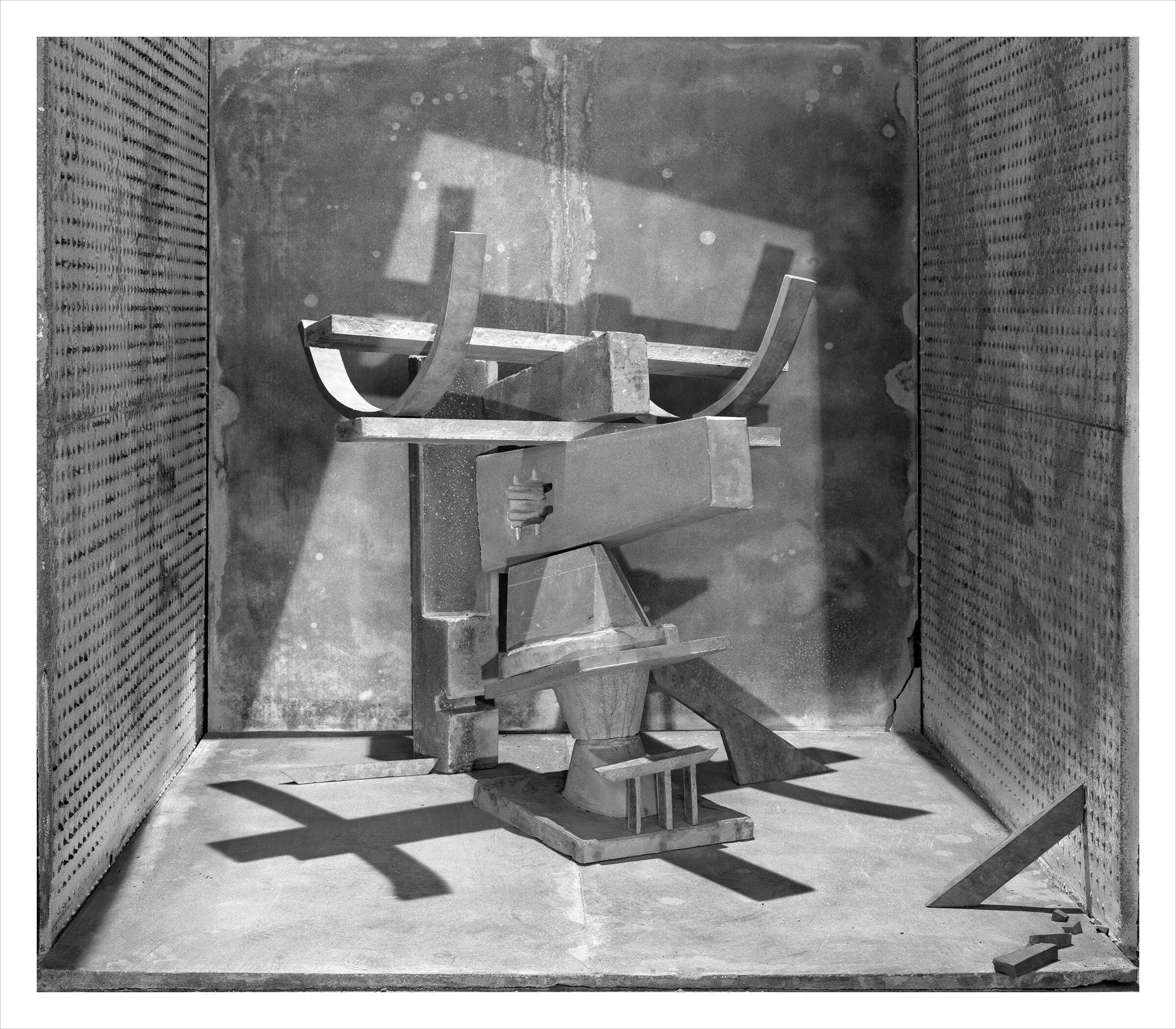

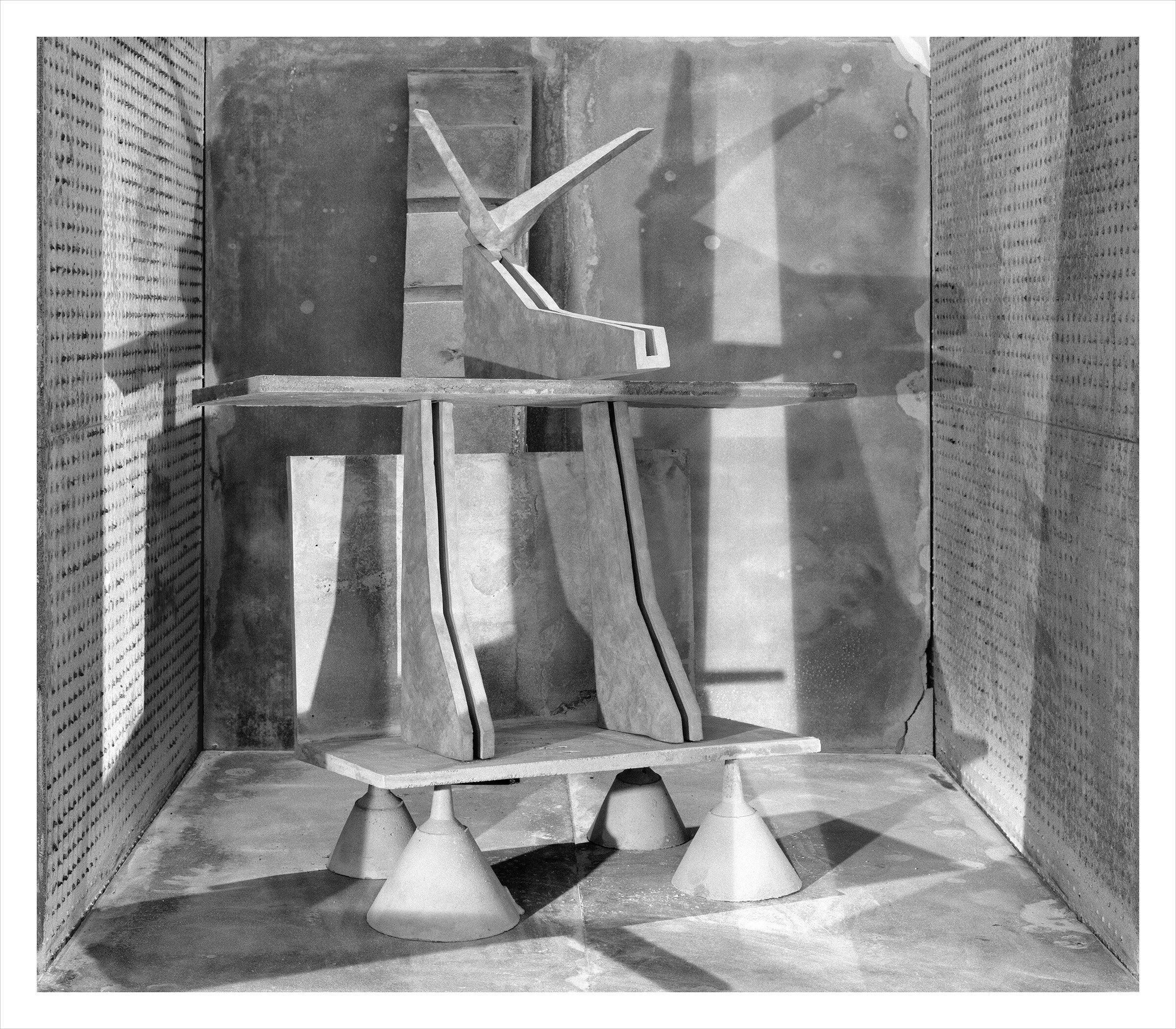

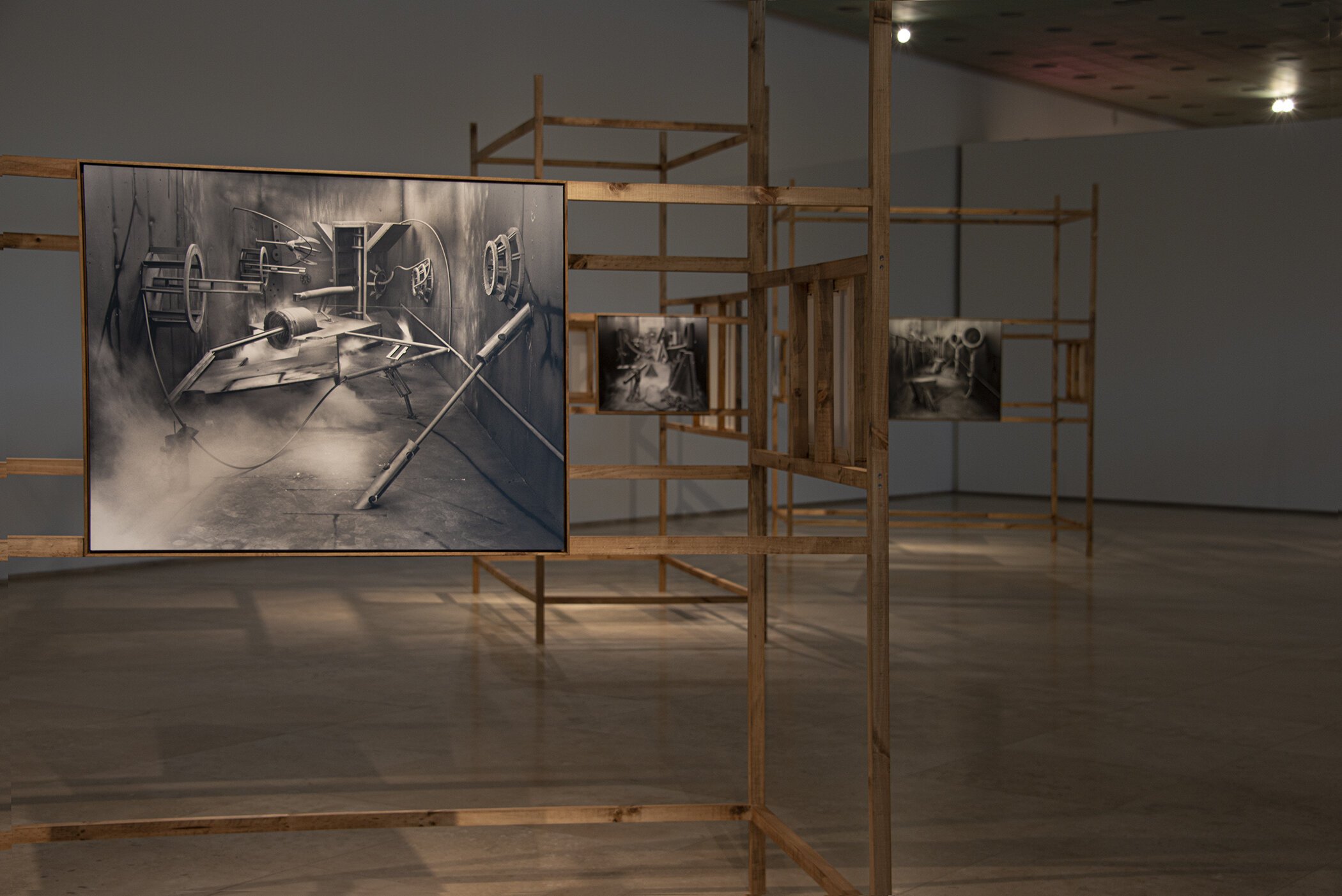

SR So this show that we're looking at now called Journeyman, I found it to be really unique in terms of your installation approach. It's really cool. So you've got your photographs on the wall and then the entire gallery floor is raised, made of plywood with these inserted boxes. What's in the boxes, these sculptures?

RV Some ceramic pieces that I made. I think it's interesting listening for the simplest sounds, like listening to your steps when you walk inside a place or making an installation where you look down – literally looking down at something where you have to really be aware of your body. If you have seen all the installations, it ranges from going around a structure or seeing a scaffolding, or feeling your steps. I like to the idea that the viewer can be aware of the body, that they walk inside a place and now they are participants of that vantage point and looking and thinking and moving around and the way they move around. The works in the wall, they are photogravures, they're like this printmaking process. You can see the indentations in the paper and then you see that it's almost like a photo, but it's also graphite-looking elements.It's one of the first ways to reproduce images.

I really wanted to feel the weight of all the work. This is actually the second part of the Trilogy of Modernism where I was thinking about Latin American brutalism and the buildings and all the Modernist buildings built during the fifties and sixties in Latin America. Coincidentally when all the countries have dictatorships. So in my mind I was like, "Hmm. The CIA..." There was this place in Panama called the School of Americas. There also was this place in Fort Benning in Atlanta that was part of this, the School of Americas, possibly where most dictators in Latin America were trained. It got a bump after the Vietnam War to really elevate the anti-communist agenda. That place has been running since 1948, so really they were running this school for assassins for a long time. A lot of the dictatorships in Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Peru—most of these people were trained in the American educational system.

SR Not surprisingly.

RV So I was thinking a lot about brutalism during that period. The coincidence between this Modernist architecture and the putting dictators all over Latin America. So I started making these statues, these pieces, they were kind of little monsters or monuments. You know what I mean? It's like a little devil. I made a lot of random objects, and they were all made out of concrete. Again, when I moved here, I worked as a concrete worker. So I know how to use concrete very well. I was just filling styrofoam packaging that I found in the street with concrete and making these little monuments out of the byproduct of capitalism in some way. So it's a lot of material mixed between the history of Latin America and brutalism and using these capitalist afterthoughts to build monuments.

SR That's incredible. Were you thinking this at the time, or did you realize it as you went along?

RV I usually start with a pretty solid foundation, but I do not know everything about it. I knew about the dictatorships, but I didn't know the shapes. So in one way that gave me a lot of freedom because there are some images that would remind me of a sculpture here, or a sculpture there. I obviously reach out into a lot of other images and other ideas. But in general, the research is there, I just didn't know the shapes and I just started playing around.

SR It's really magical. And it's so heavy and so disturbing what you're talking about. I see the connection, but because you're making art and you're creating your own experience, and then we get to experience that in our own way, that there's just so much more room in there. It's like a novel, you know? It's both fictional and real.

RV Yeah. I think that it's funny, I love thinking about that. The word "real" and really thinking about what that means.

SR I know real is… I don't have a better word than that. Maybe historical, but even that has so many versions.

RV Yeah, I think... There are flaws in everything, right? But we do not have better words for a lot of stuff. Photography has this very interesting friction with reality. I say it as a kind of jokey, slightly sassy statement about a lot of photography that is immediate — like street photography is like the Republican cousin of photography, right? And I make this very weirdly liberal work or it's slower like sand. I think because photography has this relationship with the real. So many times we associate the real with immediacy.

And we see it even with politicians, right? Where the person that says something really fast is felt or recorded as real, as more real. "Keeping It real" is saying stuff from the guts. Saying what you think is keeping it real. It's very silly because in some way, taking some time away and truly meditating about it and really thinking and responding tomorrow with that definitive answer, with what you really meant.

SR Yeah.

RV This is suddenly encountered as less real than that immediate unprocessed emotional response. And we live, the whole society is like that and I think it's really fucked up.

SR Yeah. I read somewhere that you went for a degree in philosophy, is that right? You did postgraduate work.

RV No, I was an undergrad at Evergreen State College.

SR So I don't know how to ask this. I just heard that in what you were saying. I heard a philosopher, always thinking big picture, "Why are we doing it this way?" I love the way you think.

RV Yeah. I think it's a funny way that we have to not get better at thinking through issues and really prioritizing immediacy. And also not having fear of being wrong.

SR Or make mistakes.

RV Yeah. Thinking out loud doesn't have to be bad. Even if you say the wrong thing, no one will accuse you of being dumb, right? There are a lot of components to being wrong. That is different than saying something that is not smart or something you need more time to think through. I think it's a very complicated relationship we have with reality and immediacy.

Also, artists have so much fucking time to think about this stuff and some painters take months making one painting. So whatever people call philosophy or really thinking through issues, it is a lot of time to muscle through some thoughts and to clean and dissect and elaborate on a very robust discourse. We have this weird society where intellectuality is in a position to conceptualism. So we don't even consider very heartfelt emotional components of art intellectually driven.

And in the same way that you don't want something very intellectual, we imbue with way too many emotions, right? And in some grad schools or maybe college or maybe a Western European Germanic influence that taught you that smart things have to be cold. But I really think that when you think something, you feel something, and when you feel something, you think something. There is no reason – mostly in the speed that artists work. Everything takes so fucking long. Nobody asks you to make a painting in an hour. Nobody asks you to make a show in two days. You have so much time to really meditate about the shit that you're making and why you're making it. Not sharing those feelings, it's a missed opportunity.

SR I wanted to ask you, what are your dreams? It's a weird question, right? I felt like I should ask you some really technical questions about art —

RV No, please no! I would hate that.

SR The question that I really wanted to know is, so what are you dreaming about? If you could do anything, what would you do? You know, because you're such a hard worker. You must have a dream side to you.

RV I think it's a nice question. I think I have to work hard on not letting my identity be so wrapped up in the idea of being a hard worker. Because I do... I mean, I moved here with nothing. No money, no English, nothing. It doesn't happen often that people cross the border working and don't have any friends or family or money.

SR Yeah.

RV And then being a tenured professor at the best university, having amazing colleagues, and a lot of economic stability.

SR And a pretty successful art career.

RV I'm glad that you think that.

SR Yeah, I do.

RV So I dream of finding this balance where I don't think that I'm a bad person if I'm not working all the time. If I'm not helping my students, for example. But, you know, I don't even consider it helping my students and really for most of these people, they are so smart and I would talk about that with anybody, anytime all the time. And sometimes to a fault I give a lot and I don't have a lot of space to really think through my own life and issues, so I want to find time for me. My friends and my colleagues think that I have no life and I just work really hard and only introduce me as, this is Rodrigo, a super hard-working guy.

I do have this fantasy, ever since I was a kid, to be smart—maybe because I grew up so poor that I always thought that through intellectual life I could...it doesn't mean that I would be rich, but at least I would not be concerned about money because I could be happy reading a book or watching a movie. But the earliest thought or memory I have is like that. Maybe because I saw my grandpa reading a lot and he was the only male figure I had to admire was somebody that was very intellectually driven. So I always thought that that would be a good way to escape. Not only poverty, but also just escape.

So right now, I am really interested in teaching in a way that is more gratifying with the students and to have a meaningful dialogue with them rather than a lot of shows. Definitely having an hour with some of my students is much more gratifying than having a studio visit with a fancy curator. I've been teaching years and years of undergrads and grads at UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) and at many schools, and this summer I'm going to teach at Bard. I go to at least ten schools a year teaching. Just two weeks ago I was at SVA in New York and before that I was at the University of Iowa. I do it a lot and in two more weeks I will be going to UPenn (University of Pennsylvania).

So between doing studio visits and talks, I think my art ideas make a bigger impact than being in any Biennale or Documenta or anything. I mean, you don't remember who the fuck was in the 2012 Whitney Biennial. It's just irrelevant in your life. But having a really good teacher, a good mentor, somebody that really has your back and gives you critical feedback will stay with you for 30 or 40 years.

SR Yeah. Your teachers never leave your mind, do they?

RV So I think that's what makes me really, really happy. And what I hope is to try to become a better teacher and a good ally for these people that are trying to figure it out. Because with artists it's almost like karate in some way, right? Like when you enter the room, everybody is together trying to kick really high, right? The white belts and the black belts are all together and you do the same exercise and it's not much more complicated than that—really thinking through images, talking about culture, poetics and politics, and suddenly you get really good. That point in age where a lot of people get really bad after being so good for so long because, you know, shit happens. I really am more interested in making interesting work that I want to talk about and think a lot about, but teaching is super important because I can't think of anything more important in the world than giving people the confidence to express themselves and to be their best selves and enabling self-discovery.

SR Yeah. That's amazing. You sound like an idealist. I couldn't teach school when I first got out of art school because I felt like I wouldn't be able to face myself if I told all these students they should go and become artists. I was so questioning of the whole process, like, how the hell am I gonna make a living? I can't in good conscience tell this young person that they should make a living making art, you know? Obviously I don't feel that way now, but what do you tell your students?

RV It's tough because we try to make it as affordable as it can be, the school. I try to give them tools to be able to apply to stuff and to know when they're doing something wrong, and when they're doing something right. And there are obviously recipes and techniques to make their work look professional. But the main thing is how to think through issues and I think the art thoughts will help you or some techniques will help you through life and through issues and through many different things, you know?

SR It's a way of thinking, a way of being.

RV Yeah. So I think whatever they decide to do is not my concern. For example, one of my students is now trying dancing, doing some sort of acrobatic pole dancing for Snoop Dogg and Usher. And she found that happiness by being in the MFA program. There's no one in the department that would think that she's not being a real artist because she's not joining galleries or is one of the "top 10 or 30 artists that you should know." But there is a thought behind what she makes and there is a desire to get better at it. She's having fun. She is making other people happy and I can tell she's very thoughtful about it. She has theories behind it... And I think as a feminist output and a creative output it is fucking wonderful that she does that.

Some people are showing big galleries and the open studios are full with art advisors and galleries, and if that makes you happy ... Again, there is no one else better at making Sarah's work than Sarah, so I'm there to help you to figure it out—how to be better at making your stuff, giving you ideas, resources, maybe some criticism because we need friends to tell us when our shit is dumb. You can trust me for two or three years while you're in school. That is my intention.

But I think having thoughtful people is very important and that is the extent of what I care about. Being in a university like UCLA, it's like we have the mission of trying to get as many people through the door and out of the door so they can all have this opportunity and two, three wonderful years where they can be themselves and have people who care about what the fuck they're thinking. Because once you are there, as you know… out there, not in a school, no one cares.

SR Yeah. It's hard. It is a challenging environment. I want to go to your class. I want to be back in school with you. That sounds great.

RV I try, I do get good reviews and I try, but I also try to also show how I have fears and doubts about being an artist. So it's very important because as I said, growing up in a developing country with not a lot of money or resources, I always thought that artists knew something that I didn't know. And what I didn't know is that no one knows what the fuck they're talking about. So I think you need good mentors that help you to feel comfortable not knowing.

SR Yeah, or good mentors that are so passionate. I feel like that's your secret weapon or your driving force. It seems like you have this underlying drive, this passionate feeling about your interests and you just never give up on them. You're constantly digging deeper.

RV Yeah. I think it's a good excuse to learn and discuss more stuff and have good conversations and there are intersections of course, in my work and what I want my political life, my personal life, and my emotional life to be, which doesn't happen all the time, it just happens in my case. But it is good to be able to reflect visually about how you feel about relationships and about politics and about history. Again, I started a long time ago, but thinking in a way of essays and allowing myself to just be in an idea and then in a show and then I move on.

I just want to move on sometimes from the idea, but I want to finish it. I want to finish the thought in a very strong, articulate way. And then every year I make two bodies of work, or like, sometimes more if I have a little more money, but it is kind of like having a conversation and putting it out there. And then I know not everybody's your audience, but somebody will listen and at the same time you get better at making images. So some people are seduced by the image. That makes me happy too, because I do work hard in making technically sufficient and challenging images to look at. And once the thought is there, when the confidence is there about what you are planning to think or say, what do you want people to think with the work? Not only about it, right? What do you want people to do, and you hopefully fantasize all the scenarios where you see people signing out and really spending time with your work.

SR Yeah.

RV Then, I want to make it super fucking beautiful, or interesting to look at. So I try different techniques for all the shows. Every body of work has radically different techniques, mostly based on printmaking, painting, photography and a variation of that. But they all are made with different tactile qualities and different retinal qualities. I like to fuck with the eyes and I like to fuck with the perception of people a little bit to make it more interesting to figure out what am I'm looking at and why I love it so much and why it's so shiny and beautiful and interesting. I try to do it, I mean, I want to get super good at some point. Right now it's just sufficient for the one show. But I do practice a lot on how to figure out these techniques and how to invest in my knowledge and my feelings through the materials.

SR Can you talk briefly before we end about these screen prints on top of your landscape photos? What are the drawings for you on top?

RV Those are pretty much transfer processes. Those are photocopies, color photocopies, transferred with glue. Then I make shades of gray and lines that are trying to figure out these properties, these houses, these possible cities for disappeared people in the desert.

These are the most fun projects too, because it is the only time where I don't have to research a lot. I can make them between projects and I can make them about how I feel about certain stuff or the possibilities. This has just become a real muscle exercise of skills and qualities of composition and knowledge about space. It's very free and they fail a lot and sometimes I have to fix it, but it is also about having a conversation with the mistakes you're making too.

SR That's cool. Thank you so much, Rodrigo.

RV Thank you Sarah. I really appreciate your time. It was nice to catch up too.

SR Yeah. I can't stop looking at your images. I know we have to end, but...

RV We can do another segment if this gets enough clicks.

SR Right? An encore session.

RV Yeah. We can do an encore session anytime.

SR I feel like we should hire you to do an artist critique section for the show. You know, we could have students that you could help.

RV Yeah. You know, I love doing that. I did this last year—Getty had this program where they wanted to start this program where artists would pick a piece of work and have a criticism about this piece of preexisting work from the collection. I did this, and I loved it. It was really fun. I love doing this out loud mental exercises, but I do it for a living, having crits. A lot of the time it's a good exercise for me to think out loud about stuff that has no... Like these work in studios, in an artist's studio, that you didn't even know existed. So it's the only time in life where you have the chance to encounter something for the first time and really dig hard into your pop-cultural emotional subconscious to figure out how the fuck can I help this person.

SR Yeah. And where did these ideas come from? Also, it sounds like you're not hyper critical. You're looking for a way to support them, which is obviously the intention of most teachers, but I think sometimes that gets lost in the art establishment of the university, and students end up feeling quite cut down by the time they leave.

RV I think a lot of teachers are jealous people and at mostly bad universities.

SR So if someone's coming from a bad place, it's hard for them to be supportive.

RV Yeah. It's very hard to be supportive if you don't believe in your own practice. You know, the problem is—

SR Like twofold.

RV People teach a medium that they don't believe in anymore. A lot of... You can find a lot of painters that haven't made paintings in a long time. They're making ceramics, they're making installations, or they have their assistant making the paintings. They don't believe in the project, in the mentality that is required to make some interesting work, and playing with the material. Because they're more interested in the money that they make with the gallery and they have a system making it and they're more interested in signing it and hanging out with the people of their caliber. So I think a lot of people don't believe in the medium that they're teaching. So I think a lot of students can register that. And also, there are a lot of doubts and again, you are an artist and sometimes I love to give my artist’s taste and sometimes I hate a lot of stuff and I love a lot of stuff.

I'd rather focus on the stuff I love, I'd rather make work about this world I would like to see. But also, your job maybe is, since you're a hater and you don't want to see... Maybe try to help people to not make any more shitty art, you know? So if you think the work is not going in a place you like, just support it more because the work that you love is already in the way that you think the work is. In the work, there are things that you hate, maybe try to make them aware of references, give them some extra support. Maybe that person needs to process some emotion in a different way. It is so much shit, but I think the tough luck mentality doesn't really help anybody because motivation and resources... And again, they're going to make the world that they can make, you know what I mean? They're under certain parameters, certain age, money, class, all that shit interplays when you make art. So you can't really tell them to no don't make this or this is shit without really understanding a lot of things about them first. So spending a lot of time criticizing somebody is not really fair and it's not an interesting exercise for me or for the critiquer. It feels lazy to me and it feels selfish.

SR Amazing perspective you have. I'm impressed. That's great.

RV No, no, I'm impressed. Thank you for your questions. It's nice how much space you give me to rant. I'm sorry if I took all the air.

SR No, that's the point. There's no way we can completely understand you in this one hour, but to open the door to this conversation, I feel like there are so many jumping off points. I will be thinking about this all week, so we'll be in touch. We'll continue. Thank you.

RV Okay. Thank you Sarah.